Iron Bicycles and Buffalo Soldiers

Originally posted on February 16, 2017 at 1:53 amWords by Adam Hunt, photos courtesy of Stan Cohen

“The bicycle has a number of advantages over the horse, it does not require as much care, it needs no forage, it moves much faster over fair roads…it is noiseless and raises but little dust, and it is impossible to determine its direction from its tracks… There is no condition of weather we did not endure, no topographical obstacle that we did not overcome… The trip has proved beyond peradventure my contention that the bicycle has a place in modern warfare. In every kind of weather, over all sorts of roads, we averaged fifty miles a day. At the end of the journey we are all in good physical condition… We endured every possible condition of warfare, but being shot at… Seventeen tires and half a dozen broken frames is the sum of our damage. The practical result of the trip shows that an army bicycle corps can travel twice as fast as cavalry under any conditions, and at one-third the cost and effort.” –Lieutenant James Moss U.S. Army, 25th Infantry Bicycle Crops Fort Missoula, Montana 1897

The story of the United States 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps is the story of adventure, triumph and heartbreak. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, it’s estimated that between 180,000 to 200,000 African- Americans served in the Union Army, and another 65,000 wore the uniform of the Confederacy. While exact numbers are hard to come by, it’s thought that nearly 30,000 African-American troops were killed during the conflict.

On July 28, 1866, Congress established a peacetime army, drastically reducing the size of the post-war army, and abolished all the African-American units established during the time of war. During this period of post-war construction, four new “colored” infantry units were created, comprised mainly of veterans of Civil War units and liberated slaves. Two of these newly created outfits were the 24th and 25th Infantry Units.

African-American soldiers were at the forefront of the United States’ westward expansion. The 25th was originally garrisoned in Louisiana but was later stationed in some of the most remote and inhospitable locations imaginable. The 25th was divided into smaller company-sized frontier posts. They built forts, enforced Indian treaties and guarded the Mexican border. One small detachment would be sent to one of the most remote outposts of the time, Fort Missoula, Montana.

They earned the nickname “Buffalo Soldiers” from the Native Americans they encountered. During the next 85 years, the 25th Infantry compiled an impressive history. The “Buffalo Soldiers” overcame harsh living conditions, difficult duty, low pay, and racial prejudice. The men developed a reputation for dedication and bravery. In an 1881 dispatch, Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson issued a complementary description of the 25th Infantry:

“It is a pleasant duty for me to thank the officers and enlisted men for the zeal and alacrity with which they responded to every demand…for the fortitude which they braved dangers, and the intelligent activity and efficiency manifested in the discharge of the duties assigned them.”

African-American soldiers of this time period were reported to have had fewer disciplinary problems, lower incidents of desertion, and greater morale than their white counterparts.

A New Weapon?

“Not many years ago the bicycle was looked upon as a mere toy, a kind of ‘dandy horse,’ and the riders were regarded as fit subjects for pity. That time, however, is a thing of the past; the bicycle of today is a very important factor in our social and commercial life, and bids fair to figure conspicuously in the warfare of the future.” – E.H. Boos, Daily Missoulian Military Purposes, June 19, 1897

In 1896, the bicycle was cutting-edge technology. European armies were quick to adopt this new invention. The first known use of the bicycle in combat occurred during the so-called “Jameson Raid,” preceding the Second Boer War (1899-1901), where cyclists were used to relay messages. The United States was slower to see the value of the bicycle. Despite having plans as early as 1894 for outfitting 50,000 soldiers on bicycles, the plans do not appear to have been widely accepted.

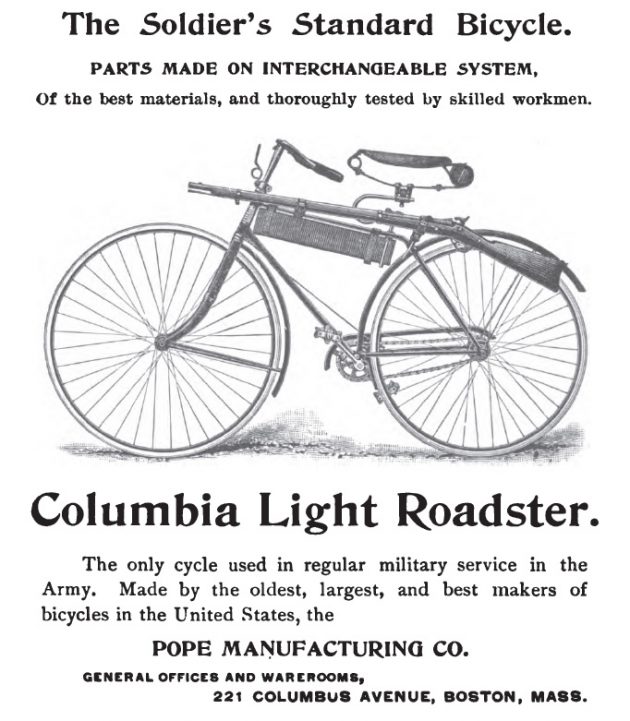

While stationed at the remote Fort Missoula outpost in Montana, a young lieutenant, James Moss, was picked by General Nelson A. Miles to explore the viability of the military application of a new contraption called a “safety bicycle.” Unlike other early bicycles such as the Penny- Farthing, the safety bicycle was a recognizably modern bicycle. These so-called safety bicycles generally had two identically sized wheels, a diamond frame, and chain drive, making them better suited to rough or non-existent roads than the giant, teetering high-wheelers.

Remote outposts such as Fort Missoula were not considered desirable commissions, and being assigned to command Black troops even less so. As a young lieutenant, the now famous General John J. Pershing was given the contemptible nickname “Nigger Jack”—later softened to the commonly known moniker, “Black Jack”—because he spoke favorably of the African-American soldiers under his command.

I interviewed singer/songwriter Otis Taylor to gain more insight about what it must have been like for the Buffalo Soldiers in Reconstruction-era America. In the early ‘80s, Taylor managed a bicycle team with a lot of African-American riders, and has written songs such as “9th Cavalry Blues” about the Buffalo Soldiers, and “He Never Raced on Sunday” about America’s first cycling world champion, Major Taylor.

Otis Taylor said that often times, Black soldiers were placed in remote locations, away from white people, because they were afraid of well-trained and armed Black men. They were given experimental equipment such as the infamous Trapdoor Springfield Model 1873 (due to the tendency of the copper bullet cases to fuse to the chamber’s walls) and were used to test out bicycles “because their lives had no value.”

The A.G. Spalding Company of Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts agreed to donate the bikes free of charge for the Moss expedition. The Spalding Military Bikes were outfitted with steel rims, chain guards, tandem spokes, extra heavy-duty forks, gear cases, luggage carriers, frame cases, Christy leather saddles, and spoon brakes. (The precursor to rim brakes, spoon brakes used a metal plate pressing on the tires, not the rim, to stop the bicycle.) Finally, each of these singlespeed bicycles was geared at a “generous” 68 gear-inches.

Lt. Moss set out a training regimen for his squad. Training consisted of 40-mile rides, and obstacle courses including a nine-foot fence men had to climb over by leaning the bike against the fence, standing on the bike’s seat, climbing to the top of the fence, then pulling the bike up and over.

During the summer of 1896, Lt. James Moss gave a dramatic demonstration of the bicycles’ potential by riding with eight soldiers from Fort Missoula on a four-day exploratory ride to Lake McDonald. The following summer, Lt. Moss embarked on a longer, ten-day, 500-mile trip from Fort Missoula to Yellowstone Park and back. Emboldened by his successes, Lt. Moss set out on an even more ambitious undertaking, a 1900-mile journey from Fort Missoula to St Louis.

The Journey Begins

Accompanying Lt. Moss on this journey was Dr. James Kennedy, who would later distinguish himself during rescue efforts during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and Pvt. John Findley, who had previously men were under way.

Early on, the journey proved to be tougher than anticipated. Lt. Moss’ journal of the fourth day set the tone for things to come:

Day four, Elliston, MT to Fort Harrison, MT

“Our rations being about to give out, the command started out again at 10 o’clock the next morning and in mud and water, for Fort Harrison, the next ration station. Three miles east of Elliston…we took the old Mullan Stage Road, which is now little more than a mere trail full of ruts, stones and dilapidated corduroy bridges. Pushing our wheels up this muddy, slippery grade for several miles was indeed, hard work. About noon the Corps reached the summit of the Main Divide of the Rocky Mountains, in an awful sleet storm, with two inches of snow on the ground. So cold was it that we would stop every now and then to strike our hands and rub our ears. The descent on the Atlantic slope was as difficult as the up-grade work on the Pacific side, as the slope is very steep and great exertion was necessary to prevent our bicycles from running away. The road is now virtually what may be called a “dry creek,” which flows quite freely in rainy weather. The snow and sleet were thawing rapidly, and for several miles we pedaled along in water and slush up to our ankles.”

The going was rough. Mean-spirited farmers gave them bad directions; they had to scrape mud, referred to as “black gumbo” by the men, off their tires with butter knives. They experienced snowstorms in the Rockies, sand and scorching heat in Nebraska, and riding on railroad tracks that numbed their hands. Men suffered the ill effects of drinking alkali water and pushed their bikes through snow, over rocks and ruts; forded streams and crossed mountain ranges; suffered from heat, cold, hunger, and the loss of sleep. “Runaways,” uncontrolled, unstoppable accelerations, were common and the men soon learned their bicycles’ spoon brakes were no match for the eastern slopes leading into Helena, Montana.

The reporter, Eddie H. Boos, estimated the men had to push their bikes somewhere between 300 to 400 miles of the nearly 2000-mile journey.

“After leaving the mountainous country the roads improved and the remainder of the trip promises to be under a sweltering sun. The men are in good spirits and health, and though some of them seemed to be trained down pretty fine, they are strong and active and able to make forced marches if necessary.” –Eddie H. Boos

On average the men would ride or push their bikes up to 50 miles a day, and held an average speed of six miles per hour. An astonishing feat considering that when, as a young lieutenant, Dwight D. Eisenhower accompanied the first Transcontinental Motor Convoy from Washington D.C. to San Francisco in 1919, the convoy of trucks averaged 58 miles per day and motored along at a blistering six miles per hour.

The bicycle convoy would periodically pass by farms and small towns. Occasionally, farmers would let the men stay on their land and give them something fresh to eat or simply ask questions. When a civilian asked one of the men, “Where are you going today?” the riders quickly shot back, “Lord only knows—we are just following the Lieutenant.”

The Final Miles

Forty-one days after the expedition left Montana, the men finally reached their destination. Upon reaching St. Louis, the men were treated to a hero’s welcome. Boos tells us that as the men reached the end of their journey, the Corps were escorted by hundreds and were welcomed by over 10,000 people upon reaching Forest Park.

After the demonstration, things initially looked promising for the 25th, but that initial optimism was short-lived. The Spalding bicycles were soon packed up and returned to Massachusetts and the men returned to Fort Missoula by train. Lieutenant Moss continued to study German, French and British military cycling strategy and submitted a proposal for a twenty-man ride to San Francisco, but with the onset of the Spanish-American War, that proposal was permanently shelved.

Within one year of returning to Fort Missoula, the bicycle corps was disbanded, and the 25th was deployed to Cuba to fight in the Spanish-American War, where they played a key role in the capture of San Juan Hill (before Theodore Roosevelt and his so-called Rough Riders).

After the Spanish-American War, the men of the bicycle corps went their separate ways. Haynes ranked highly as a marksman and was described as an extremely capable noncommissioned officer. Private Eugene Jones was wounded in action in Cuba and private Elwood Forman died in the Philippines in 1901.

Sergeant Mingo Sanders would be dishonorably discharged on a trumped-up charge surrounding a shooting incident in Brownsville, Texas in 1908. A white bartender was killed and a white police officer was wounded. Details of the incident are hazy, but it’s generally thought that no African-American troops were involved in the shootings.

Despite pleas from Brigadier General A.S. Burt on the behalf of Sergeant Mingo Sanders, “the best noncommissioned officer I have ever known,” Sergeant Sanders, along with 166 other African-American soldiers, was dishonorably discharged by order of President Theodore Roosevelt. It was not until 1972 that the Brownsville injustice was corrected and all 167 men received honorable discharges.

In the end, Lt. Moss concluded that the only use for soldiers on bicycles was as messengers or scouts to compliment cavalry and infantry. The Army saw little need to continue using bicycles, as horses were plentiful and roads so poor in the western United States.

But the real legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers is one of overcoming nearly impossible odds, and the fight for dignity, honor, and civil rights in an era where the majority of the population was actively hostile towards their fellow human beings.

The Things They Carried:

Every man carried a ten-pound bedroll, a canvas tent, tent poles, a set of underwear, two pairs of socks, handkerchief, towel, bar of soap and a toothbrush, all fitted into a luggage carrier in front of the bicycle’s handlebars. Each squad chief carried a comb and brush and a box of matches. The troops filled their bags with flour, baking powder, dried beans, baked beans, coffee, sugar, bacon, canned beef, and an allotment of salt and pepper. The bikes weighed about 59lbs. and each man carried a 10lb. Krag-Jørgensen rifle and a 50-round cartridge belt.

Author’s Note: Special thanks to Mike Higgins, whose blog was a key source of biographical and timeline information for this article; to Jason R. Bain, Curator of Collections at the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, Montana for the image files to this story; to the people of Pictorial Histories Publishing Company of Missoula, Montana for their hard work; and to Otis Taylor for taking a last minute phone call from a stranger.

This story first appeared in Dirt Rag #154.