Understanding Floyd Landis

Originally posted on December 12, 2016 at 9:48 am

Words by Chris “Bama” Milucky

Photos by Devon Balet

It’s not that I hate roadies, but some are pompous, and the most famous has a reputation—now bordering rap sheet—for lies, manipulation and legal threats. So when my editor, Mike Cushionbury (Cush), called at exactly 4:20 p.m. and told me Floyd Landis was starting a marijuana-product manufacturing business (vape pens, edibles, etc.) and asked me to find him and do an interview, I wasn’t sure I wanted that kind of trouble in my life. I’m not short on friends, and I’m not famous. I live unnoticed, off-grid, under the radar, and I’m liable to show up in your driveway on an overloaded motorcycle. I really don’t want a “zillionaire” roadie suing me because of an interview I did in a small, independently owned magazine. Besides hearing his name in the context of the Tour de France (which I’ve never bothered to follow), I had no idea who Landis really was, much less who he is today.

Before meeting Landis, I wanted to know he was safe. I knew Danny Pate from mountain biking in Sedona, Arizona, and that he had raced in the Tour as well. I sent him a Snapchat, hoping to get a green light. Danny was too busy messing around with dirt bikes in Durango. Next on my call list: Kiel Reijnen, another UCI World Tour-level pro. Last time I talked to Kiel was when we were in college. He called around 3 a.m. asking to borrow a cargo bike.

“What’s going on? Why do you want my cargo bike in the middle of the night?” I asked.

“Because I’m trying to prove that running is easy; if I run an off-road 30 miler tomorrow and qualify for the Boston Marathon, some guys at this party are gonna give me $100! My friend Blake wants to ride the bike and carry my food, water and boombox.” I knew if Kiel said Landis was trustworthy, it was solid info.

After a few rounds of texting and a downloaded internet phone app, I made contact with Kiel while he was training in Spain. He said Landis was crazy, but in the same way that he is—the same way that I am. The same way that all of us with a thirst to live are a little crazy.

“He’s one of us.”

Game on. I looked up Landis on Instagram, Googled his business name, got an address in Leadville, Colorado, and two hours later I stood outside the former-house-turned-office for Ski Cooper ski resort, soon to be Floyd’s of Leadville.

It was a dingy white building in need of paint, new windows and a sign—not to mention a dumpster to fill with the remnants of items left by the old tenants. I didn’t know what to think.

Why Leadville? Is there some sort of elite racing scene I don’t know about? Perhaps the pros have a summer training camp up there. Or maybe it was a tax haven for Landis’ millions of dollars. Who knew?

At any rate, Floyd’s of Leadville scheduled a product launch in Denver, and I was going. It seemed legit, so I propositioned a team of three. My idea was to ride bikes to the event, sample the product and establish a rapport before conducting an interview. What actually happened pissed me off.

For starters, we were the only ones who rode bicycles to the bar. Secondly, Landis barely so much as shook my hand. There weren’t any products to see, much less try, and we were granted no more than one free drink and handed a “Floyd’s of Leadville” T-shirt. Only out of coincidence did I chat up the door guy, who told me if I beat the bartender at rock-scissors-paper, I could win a second free drink, which I did.

The next day, I told Cush I wasn’t doing the interview.

“Put your ego to rest; you gonna do the story or not?”

“I’ll do it for you, Cush.”

Reluctantly, I scheduled an interview for Wednesday at Floyd’s of Leadville headquarters. Tuesday night, Landis rescheduled for Friday. I was ready for a no-show.

On that Friday Landis arrived 30 minutes early and 30 pounds heavier than any road racer I’d ever

seen, rolling up in a lackluster Volkswagen SUV with tires riding the wear indicators. I approached him.

“Hi, I’m Bama.”

“Floyd, nice to meet you. Umm, I don’t have the keys to the building; hold on a sec while I climb in through the kitchen window.”

Without ado, Landis busted open the front door from inside, welcomed me and pulled out a pre-rolled joint from a Denver dispensary. Before I knew what happened, we dove headfirst into stories of Gene Oberpriller, former pro mountain bike racer and current owner of One on One Bicycle Studio in Minneapolis, and recollections of Hurl Everstone from Cars-R-Coffins and Paul Zeigle, current brand manager of Surly, about a night of throwing a brand-new bicycle off a parking garage. I was at ease now.

Floyd: Hey, let’s go to the pub and get some snacks.

Bama: OK.

And just like that, we were off to the races.

You went from biking around the neighborhood to mountain bike racing. I understand your Mennonite family wasn’t into racing, but they loved you and supported your endeavors. How did you leave the trails and wildlife of rural Pennsylvania and begin traveling across Europe?

Well, I heard San Diego, California, had nice weather and I had some friends down there, so I left home. It wasn’t that I hated home, I was just chasing the dream.

Did you have a job? How did you make money?

I was able to make ends meet by winning mountain bike races.

Then how on earth did you wind up on a road bike?

Ohh, you know, people said, “If you wanna get faster on a mountain bike, you have to train on a road bike.” Turns out, I was better at road racing than mountain biking.

I’ve only been to one foreign country—Mexico. I swam there and …

You swam to Mexico?

Yeah, I was on tour, doing mountain bike demos, went down to South Texas and swam across the Rio, so …

What? What’d you see? Was anyone there?

There were some cowboy ruins, but otherwise it was just a vacant desert. Point is, I can’t imagine leaving the States and traveling around the world. I can’t imagine traveling across Europe. What was that like? You grew up in a small town and then you were flying around in private jets and helicopters.

OK, I’ve done a lot of races, and forgotten most of them, but I remember the first one I did overseas. It was so muddy, I had to carry my bike, and the traveling overwhelmed me, which really wore down my mind. I didn’t do very well in the race. Later on, I became famous and it was crazy! It was like I was a rock star; people knew who I was and wanted autographs and stuff. I never really imagined I’d do anything like that, but it just happened.

You know that terrible music they play at races?

Horrible!

Did they play that crap in Europe?

Yeah! They played awful French dance music in France, awful Spanish music in Spain. That music is the best reason to leave the starting line!

Did your Mennonite mom visit you in Europe? What did she think of the whole scene?

In their [Floyd’s mother and father] religion, they don’t really listen to music, and the Mennonites don’t really like a deep beat or bass, so they didn’t like it all. I hired someone to take them around and they liked the places they went, but they were happy to get back home.

What was the first drug you did, and how old were you?

Coffee; I was 19 or 20 when I first had caffeine. Then testosterone cream and the other performance-enhancing drugs. They should count prescription pain meds more than the others, but they don’t count that. Those things [prescription painkillers] are way stronger than anything else, but nobody cares about that.

What about weed?

Probably at 30 years old.

What about mushrooms?

Never had any. Do you have some? I’d really like to try that.

Ahh, no … I’ve never brought drugs to a marijuana manufacturer.

What does your mom think about all this?

At this point, after all the crazy things that have happened to me, she just laughs and accepts me for who I am.

So what happened after the drug bust and all that? It makes sense to me, doping was part of your job. Carpenters pin back the guard on their saws, electricians wire buildings with the power on, truckers lie on their hours …

It was terrible. I was asked to do a job, and if it wasn’t done on time, I’d lose my job and my job was winning races. Yeah, what we did was illegal and dangerous, but that’s what we did to stay employed. I thought everybody knew we were using drugs. At that time [2007, a year after Landis won the Tour de France and was subsequently stripped of the title] social media was a new thing and I had all kinds of people who’d never met me saying terrible things online. I felt like I had to give everyone an answer, but every time I turned around, I’d read another comment from someone else I’d never met, who’d never raced at that level, who had an opinion on what I did. I left it all; I left cycling and moved into a cabin in rural California. For three years I ate pain meds and drank whiskey. They say that’s bad, but you can do a lot of healing with that stuff. I drank my way out of depression and the weed helps with my hip. [In 2003 Landis fractured his hip. Osteonecrosis developed and he underwent hip resurfacing in late 2006. As an alternative to conventional hip replacement, the surgeon saws off the top of the thigh bone and replaces it with a metal or ceramic ball. —Ed.]

You actually drank your way out of depression?

Yeah, I was a pretty miserable wreck, but every morning, I’d show up at the bar, spend all my money, go home and drink some more. Besides “Floyd,” nobody knew who I was. They didn’t care about the Tour de France. The people in my neighborhood didn’t really care about anything. In fact, one time I had a guy come over to work on my deck. Somebody asked him if he had a building permit and I swear, he went to his truck, came back with a gun, began to polish it with a rag and pretended like nothing happened. He did a pretty shitty job on my deck.

So what are you doing now? Are you back to riding on the dirt?

Man, I quit riding, but I should get back into mountain biking. My hip’s pretty messed up, but I should get back on a mountain bike. I miss the freedom, I miss exploring the woods.

Who would you ride with? Old friends? Or would you ride by yourself?

I love solo rides. You can go at your own pace and spend time reflecting on life and thinking about things, but if I was gonna ride with somebody, yeah, it’d be old friends. There’s just something about spending the day with your buddies riding good singletrack.

Is there anything more you’d like people to know?

Yeah, I’d like people to stop and think, “Maybe there’s more to the story than Lance Armstrong and drugs.” I keep hoping that people will think, “This dude’s a human.”

Landis generously paid the tab, and we went back to his new business headquarters.

OK, so I have this column in Dirt Rag. There’s already a bunch of crap written about bike nerd stuff so I try to write about social issues, but there’s something that I’ve had a tough time writing about: mental health. How do you feel about suicide?

After the doping thing, I lost someone close. It was tough. People get weird about that stuff. About suicide. And sometimes it just isn’t worth living. I don’t know why he killed himself [Landis’s eyes begin to tear], but that decision lies with the individual—“we” don’t get to choose whether or not “you” live.

I completely disagree with [the act of] suicide, but more than anything, I want an open communication with people. Can’t we all learn to speak our hearts?

No. People aren’t ready for that.

Why not?

Landis just stared off into the distance with no answer.

Thanks for opening your heart, I genuinely respect that. How about we take a look around this dive you just bought?

The previous owners said they’d remove all this junk, but hey, some of it’s pretty cool! Check out this box of knickknacks!

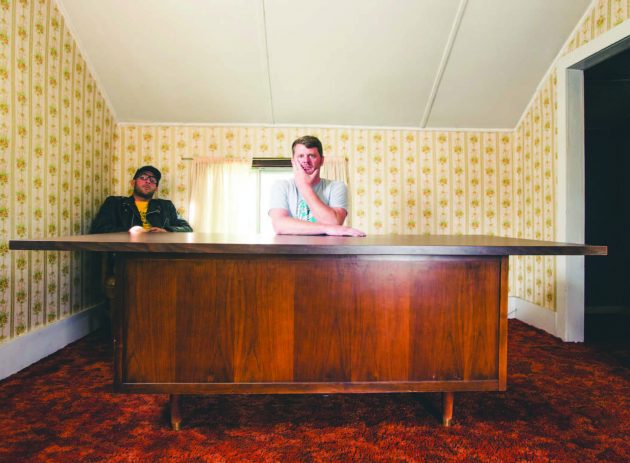

We wandered around the intestines of his most-likely-haunted building. It was layered in years of wallpaper, littered with discarded furniture and smelled of grandpa’s gym shorts. Before this interview, Landis had never even bothered to explore the basement, which, as we discovered, was chock-full of old wire, jars of nails and all sorts of weird stuff. It didn’t make sense; why did a world-traveled World Tour racer buy a derelict building in a run-down mining town at 10,000 feet above sea level two hours from Denver? Yet everything about it made sense. Everything about his weed business made sense.

Everything about Leadville made sudden sense. Floyd Landis is actually one of us. He drinks coffee, hoards bicycle wheels for no apparent reason and isn’t looking forward to the hours and hours of repainting the walls in the building.

If you think the business is about getting high and having the munchies, you’re One of Them. First of all, Floyd Landis was never supposed to win the Tour de France. He’s brilliant and he’s got the physiology, but his heart is too soft. He’s a misfit. He was a lone wolf swimming in a school of sharks. Via contracts, drugs and the machine that is the UCI World Tour, he strapped on wax wings and flew away from Pennsylvania. Before he knew it, he’d hauled ass up the Hubris Hill Climb. Floyd Landis is a turbocharged, nitrous-injected, overbored Harley mated to a lowly four-speed transmission. He’s the Ozzy in a “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath.” You don’t understand him. I don’t understand him. Despite her efforts, his own mother doesn’t understand him—she loves him dearly, but just doesn’t understand him. I’d never met the guy, and I hated him. He dissed me at his product launch, and I assumed he was just another roadie prick. I was way off. I misjudged someone who should never be judged. Someone who should simply run wild and free. Someone who’s worked hard his whole life.

Hip pain permitting—and I sincerely believe this marijuana venture stems from an unpleasant experience with prescription pain meds—I hope Landis hops back on a mountain bike and disappears into the trees. I hope he explores new trails, takes pictures and throws some solid high-fives. I hope he crosses paths with some potent poison ivy and then gets a flat tire. I hope he eats a peanut butter and jelly sandwich at a scenic vista and lays a cool skid mark in the parking lot. I hope you ride right past him without even knowing it. I hope Landis can experience the anonymity which normal people take for granted.

So why Leadville? Because it’s a place where we aren’t. It’s a place where he can be true to himself. It’s at least a mile higher than social constructions or dress codes. In Leadville is a place we will probably never visit called Floyd’s of Leadville. It is a self-built sanctuary in which Landis can speak his mind, work under his own terms and earn an honest living. I wish I’d asked him if it was worth risking and then losing it all over the Tour de France. Over stupid road bikes. But I know what he’d say…You know what he’d say.

Landis’s trip from adolescence to adulthood is what life is all about. From day one Landis rode against his family, against foreign nations, against the wind, against the rules, against pretensions and against us—the court of public opinion. Know what? He still won, so fuck it.

He’s working on products that he cares about. He wants to help other people and provide an additional pain management option, and he’s doing it his way. Isn’t that the dream? We should loosen our grip on the rules, judge others less, and ride with the same fury and power that pushed Landis from Pennsylvania to California. Through Tour stages, from innocence, through suicide, through litigation and into a small, servile, privately owned business. If we can’t learn to love Floyd Landis, to love a free drink and a complimentary T-shirt, then we’ll never really get it.