Feature: The Crossroads of Beauty and Insanity

Originally posted on August 9, 2016 at 11:51 amWhat it was like to help start Independent Fabrication

Words: Steve Elmes

Photos: Jasen Stickler

Originally published in Issue #192

“What the proverbial fuck?” That’s pretty much what I thought the moment I was told that Fat City Cycles would be shuttering its Somerville, Massachusetts, doors and, in the process, laying everyone off.

I had just spent the better part of a year of my life trying to get a job in the bike industry. I bought every magazine and called every frame builder that advertised—and I mean every single one. I got a break. I had finally made it. I was working in the bike biz and for Fat F’n City Cycles. I was giddy beyond belief, and then it all fell apart. Who knew that moment, one that by definition should have been the worst of my then 26-year-old life, would in turn prove to be the greatest?

My name is Steve Elmes, and I was one of the co-founders of Independent Fabrication. It’s been about 15 years since I left IF, packed my bags and headed west. So everything I’m about to write has been filtered by years of experience and perspective. This isn’t a tell-all article; it’s simply my attempt to answer a question posed to me by a friend: “How the hell did IF become IF?”

Oh, man, trying to describe that is akin to asking how many licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop. I’ll try to tell you, but unless you are willing to start licking, you’ll never really understand. Ask any of my partners and their answer to that question will most certainly be different. It’s a complex story to try to make sense of.

I think about the fact that when we started, the internet didn’t really exist. Everything was different. The relationships which defined us and built us weren’t digital bullshit; they were real, honest-to-goodness, face-to-face, get-drunk-together, fight-together, ride-together, do-dumb-shit-together, have-each-other’s-back relationships. The greatest friends I have on this planet are because of that company, that time in my life.

The beauty of IF is that it probably should have failed and it didn’t. It rose from those proverbial ashes, and it was wonderful. We were dealt a crappy hand at Fat City. Nobody’s fault. Business is business and that happens. How we reacted? That is what I know set us apart. It was a perfect storm of the right people in the right place at what should have been the wrong time, ignoring everyone around us and making things happen. Probably not repeatable. And it was hard. The hardest thing I’ve done in my life.

It was 1994. Somerville was an incredible hotbed of frame building and continues to be so to this day. As a result of Fat City closing, I was unemployed, along with my future partners, and I had somehow convinced them that I could handle all the sales and marketing for IF. Truth be told, I didn’t know that much about marketing. Brand building? That term wasn’t a part of my vocabulary.

What I did know was that I could talk to people. I was smart. I was honest. I stuck by my word. I was driven. I loved bikes, and I had an unwavering belief that this was a good idea. I mean, seriously, it never crossed my mind that starting a company at 26 with folks I had only known for a year and with barely any experience of my own was anything but the grandest of ideas.

Most importantly, I was scared about being unemployed; I was broke and hungry. I wanted to be in the bike biz more than anything, and nothing was going to stop me. Youthful naïveté is an incredibly powerful thing.

When I think about what built IF, I often think about the things that tried to tear us down. It was the hard stuff that made us great. Back then, IF was an employee-owned and -operated company, with everyone equal and everyone doing what they had to do to make our idea a reality. That single decision, to be our own bosses, was no doubt the single most defining decision we ever made. More on that later.

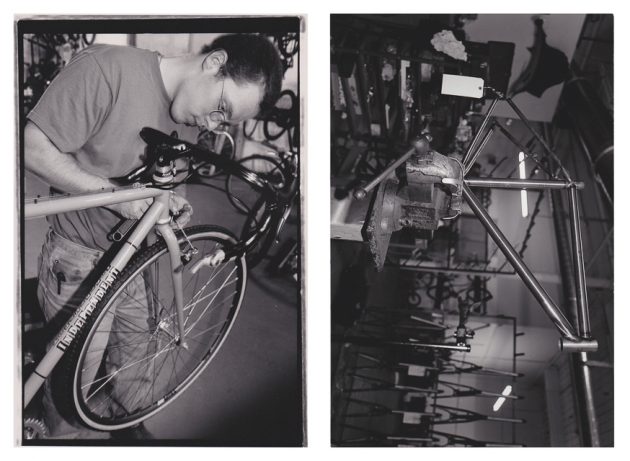

In the early days the easy part, for me at least, was knowing that our bikes were the best. They had to be. We were all ex-Fat City employees and the expectations from the industry were incredibly high. I just had to sell. As for our well-known frame builders Lloyd Graves, Mike Flanigan and Jeff Buchholz, words like “artisan” or “craftsman” didn’t even begin to describe them. To this day I am still humbled to have been able to work with them. They lived and breathed bikes. They churned out works of art under ridiculous conditions.

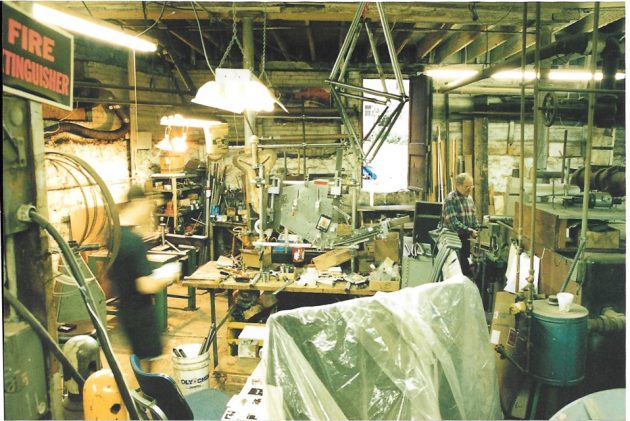

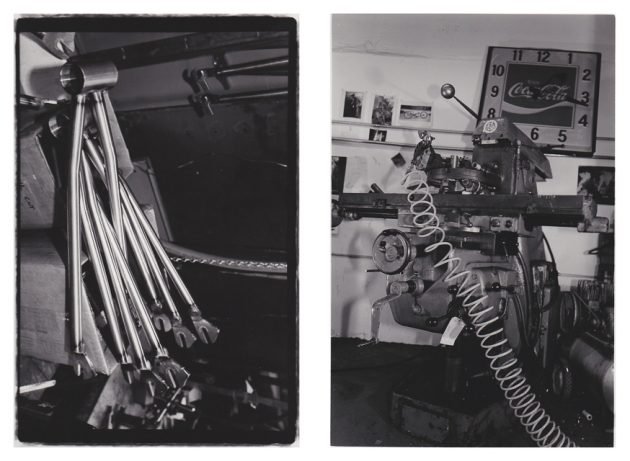

Our first space was in Dorchester, in a corner of a dingy, dirty basement machine shop called the Nexus. Tooling was built from scrap metal we secured by any means possible. Late-night raids to the scrap-metal cars parked in the train yards were a regular occurrence. Machines were bought at auctions for pennies on the dollar and made to run.

Mike would build frames all day with the guys, borrow my truck, drive to Hot Tubes in Worcester, where they can custom-paint and restore anything, paint for 24 to 48 hours straight with little to no sleep, drive back to Dorchester where we would prep frames, pack them up in frame boxes we got from local bike shops and ship them out to waiting customers. Seemed normal at the time, and it was.

Everyone worked other jobs, and IF ran at the oddest hours in any given 24-hour period. We hardly saw each other; we just trusted each other to finish what needed to be done. And it worked. I share that snippet of history because I feel it’s necessary to answer my friend’s question and to paint a picture of what it was really like in the early days of IF: chaos and trust and progress. It was hard. It was exhausting. It was exhilarating in a fly-by-the-seat-of-our-pants sort of way.

We fought with each other a lot. Employee ownership brought a lot of that about. Equality isn’t always a good thing, but it can have lasting impact that was never imagined. We were five individuals, each with our own vision of what IF was going to be. Through conversation, oftentimes heated, we tried to find common ground and ideals for our company. That’s not an easy task by any stretch of the imagination— equality among employee owners should have sunk us. No leader. No individual decision maker.

At times it certainly paralyzed us. But it shaped us, too. It kept us from being stuck on a single vision. We stayed open to ideas. We had to. If it could help us sell a bike or give us a reason to talk to someone, we’d go for it. We placed almost no limitations on ourselves and relied on a collective gut to guide us.

We made it to Interbike in 1995 and truly took our first steps to becoming a recognized frame builder, albeit different from anything the industry had seen at that time. Granted, we were still mostly referred to as “those ex-Fat City guys.”

For the next several years we grew by leaps and bounds. The industry and our fans shaped our name from Independent Fabrication to Indy Fab to simply IF. It was organic and awesome. A clunky 22-letter name, a literal interpretation of who we were, had become the de facto cool company. We found a shop with windows and sunlight next to the railroad tracks. That was nice. Our ragtag team of racers spread the gospel of IF like something out of the Book of Revelation. Dealers signed on. We hired our first, second, third, 10th and more employees. The industry and our customers rallied behind us and IF started to become IF.

It’s hard to describe that time because it is in many ways humbling. The new employees embraced the ownership vision and new ideas flooded in. New arguments, too. Beauty and insanity meshed together. Folks were getting IF tattoos. Our trade show booths were swamped. We were fucking kicking ass and it was fun! Mostly.

To this day, I recall the sheer elation the first time I saw someone riding one of our bikes and I didn’t know who they were. Someone bought one of our bikes? WTF? We leveraged every opportunity we could to promote ourselves without fear of repercussions, because we were always evolving. We were serious about what we did but never took ourselves seriously. We remained humble, and damn if people didn’t rally behind that.

Brands today feel limited by comparison, and it saddens me. The insanity of ideas we embraced still makes me laugh. Cow-painted bikes? Sounds like a great idea! The flashiest cross kits anyone had ever seen with racer’s names big and bold across their asses? Heck yeah! Singlespeeds. Twenty-four-hour races. The Leadville 100 on a tandem? Definitely. Work five days a week, run our race team on the weekend, maybe race ourselves, repeat for years on end? Sure!

We threw parties at Redbones BBQ because they loved bikes, and it became our home away from home. To the best of my knowledge the crappy BMX bike Mike painted with our logo and hung outside their front door is still there today.

Every decision we made, regardless of how it might have seemed to outsiders, only added to our reputation. There was something special about the lack of guidelines we applied to ourselves. And I am 100 percent confident today that had we tried to shape any of that, had we actually thought about what we were doing—poof!—it would have all blown away. I look back on it now and think about how incredibly simple it feels. And in many ways it was.

What made Independent Fabrication IF? In looking back I can boil that down to one insanely lucky decision: employee ownership. Despite all its challenges, the chaos it often created, the fights we had, that decision created an environment of limitless ideas and vision. It attracted bright minds and talented people who wanted their voices heard and wanted something beyond a paycheck. It guaranteed that IF would live, even when folks like me left. Perfect.

I left in 2001. Lloyd, Mike and Jeff, along with Matt Bracken, Tyler Evans, Jamie Medeiros, Shawn Estes, Jane Hayes, John Barmack and countless others continued to take IF to unimaginable heights, far beyond what I had done. Soaring. IF grew, as it was always meant to do, even if we hadn’t really planned for that. Coal doesn’t always become a diamond, but on that particular day in 1994, it did. A diamond called Independent Fabrication.