Feature: The Legend of Victor Vicente of America

Originally posted on April 26, 2016 at 17:16 pm

Words: Christopher Harland-Dunaway

Photos: Toby Kahn and courtesy of VVA

Victor Vincente of America, a man born as Michael Beckwith Hiltner, stood on a dirt road that runs along the small mountaintop valley he calls home most of the year.

“I mean look at this party!” he implored, as much to me as to the distracted world around us. The valley air shifted in an almost supernatural response. Crickets sang, the dry grass fluttered, unkempt grapevines stood in repose on their trellises, and the pine-covered hilltops locked fingers with a cloud-scattered sky.

“Let me just be really candid and say lots of times I feel like I’ve had just about enough of life. Not a lot more I really want to do. If I can just see my book in print, I’ll be happy. It’s always hard to think about leaving the party—that’s the way I refer to dying—just a party here!”

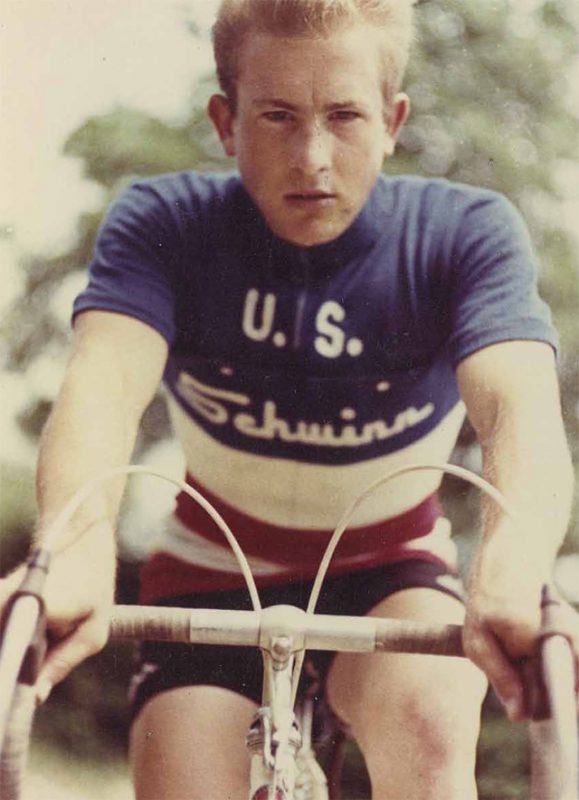

It’s been an eventful and creative trip for Vincente. He is now 40 as his current self, who began with a long stumbling, victorious and eager 34-year stint as Michael Hiltner. Together, the two personalities combine into a man that is 74. His journey from road cycling to pioneering one of the first mountain-bike frames, and being one of the first mountain bikers, has earned him notoriety, even legend.

Hiltner grew up without his father in the postwar Los Angeles basin. Imagine suburban tract housing purchased by new families on a GI Bill in the arid hills beyond the breezy coast of Santa Monica. Think pomade-structured hair-dos, “that’d-be-swell-Dad” vignettes of 1950s California. Amid an era unrivaled in its conformity and material aspirations was where the fates dropped Hiltner.

At high school he was unequivocally a loner. One of his only friends was obsessed with medieval warfare. Sometimes he played chess, but there wasn’t much to his social life beyond the cowboys-and-Indians games he had outgrown. “Nature Boy,” as his classmates dubbed him, ate lunch alone everyday by a little spring that trickled fresh water from a concrete spout, surrounded by pine trees. He loved it for reasons he wasn’t able to articulate at the time, but now he emphatically says, “It was nature!”

Grasping for nature epitomized the way in which Hiltner made discoveries throughout life—pursing ideas with visceral impulsiveness. So Hiltner decided that he was going to ride his bike to school. High school was an awkward age to be seen riding a bike. He did it anyway, undeterred.

On his ride home, he was chased down by another bike rider, who suggested he try racing. The rider was Dave Waco. Waco was prominent in the Santa Monica Cycling Club. For the ’50s, though, he was an aberration— shaven legs, kit and simply riding a bike, especially as an adult. Vincente remembers the colorful pages of cycling newsprint that Waco obtained from France.

“There was Coppi and Bobet and Anquetil in full color, glistening with sweat with their race-horse legs. We were doing little races, 10 miles; these guys were doing the Tour de France— that was unimaginable.”

Right away, entire lists of regional championships were sucked into the victorious Hiltner dragnet. At the 1959 Southern California Grand Prix, he met a rider from Northern California named Lars Zebroski. Zebroski persuaded Hiltner to come north and train to make the 1960 Rome Olympic team. Italy was the crucible of road cycling at the time. To succeed there, or just make it there, meant everything.

Zebroski was often quiet but intense and irreverent. He masterminded the Olympic effort for Rome, which depended on a two-man time trial at the Olympic trials to decide two of the 14 total roster spots available. Zebroski and Hiltner moved into the Santa Cruz Mountains and created a training hermitage along Tunitas Creek. Here among the redwoods they lived a borderline ascetic lifestyle in which they bathed, showered and washed their clothes in the brisk wintertime creek.

As they forged themselves into Olympians, they depended on cheap cheese from a dairy farmer down the road. The farmer offered his skim milk for free. Zebroski would sometimes go down the road with a peanut butter sandwich to make himself thirsty, so he could chug as much skim milk as possible. Hiltner’s favorite cheap ride food was a carton of concentrated pineapple juice with cottage cheese mixed into it.

The two lived minimally, but richly, and dreamed of the games. The Zebroski-Hiltner two-man time trial smashed the Olympic trials and punched their tickets for the ’60 Olympics. When they arrived in Rome, the city was wilting under an oppressive late-summer heat wave. The Olympic Road Race was a sequence of staccato images of flashing musculature glossed in sweat, drenched in suffering. Hiltner finished 24th.

For a long time, his result was a source of inspiration for emerging American riders; ironically, the judges made a mistake and Hiltner was actually lapped. With the games over, Hiltner, Zebroski and a crew of itinerant American bike-racing expats stayed on. They spent their first evening feasting with the famous Signore Cinelli at his villa in Tuscany. They left with factory-priced Cinellis, the best in the world.

Hiltner dove headlong into his first season racing in Tuscany. Once adapted, he learned how to sniff out breakaways and use his penchant for suffering to great effect. He won solo one occasion by riding everyone off his wheel in a hilly finale. By the end of his first campaign he won four races, a pioneering accomplishment. The dumbfounded Tuscan press noted, “And who in America could have possibly taught this young man how to race a bike?”

During the winter offseason, Hiltner fell in love with a girl who worked across the narrow street from his house. Her name was Leda. Leda visited Hiltner’s room at the villa, where they talked for hours. By this time, his Italian had gotten pretty good. The two took frequent trips into the countryside on his roommate’s BMW motorcycle, a shaftdrive 500 cc BMW motorcycle. But Hiltner struggled with the awkwardness of his socially cloistered suburban upbringing.

“I remember lounging on the bed with her and feeling loving, when all of a sudden something loud fell somewhere in the villa. It completely ruined the moment,” he recalled. “That didn’t work out there. When the racing season got going I was out by Pisa so I didn’t see her much.”

Hiltner, or Victor Vincente as he stood in his small kitchenette, exhaled wistfully, breaking the Italian reverie. He turned to the photographer and me and asked, “Would you both like some hot cocoa?” I had brought a gallon of milk at Vincente’s request: 2 percent, nonorganic. When he saw the white jug he cried, “Milk! I haven’t had milk in weeks!” As he finished up the hot cocoa, using obscure ingredients such as Chinese five spice, he paused and turned to us, saying, “I usually finish it off with a splash of rum.” He tipped the Kings Bay into each drink and distributed the mugs, leaving the last one, his favorite, for himself. It read “I love crosswords” on the side.

He also has a pair of pajama pants with a crossword pattern. He has taken a pen and written his name through the crossword boxes, and over time, found ways to intersect the names of the many lovers with his. Vincente has had three wives since leaving Italy, and many more lovers. The concept of free love and multiple lovers became a hallmark of the Vincente persona. He considers monogamy more fraught than society generally believes.

“A certain percentage of men, it’s either in their nature or they learn how to focus on one woman and that’s plenty. I never learned that,” he put it.

Hiltner’s Italian adventure started to go flat after he began to use amphetamines while racing. “It wasn’t such a taboo subject, but other teams didn’t mention it outright. They’d joke around on the starting line. ‘Quante pastiglie prendete oggi?’ How many little pills are you going to take today? It’s like drinking a lot of coffee. I’d stay up all night after races sometimes, staring at the ceiling.” After winning four races in ’60 and two in ’61, the season of ’62 was a bust. Hiltner didn’t win any races in Italy and returned to California to recuperate.

“Would you both like to go for a walk?” Vincente suddenly asked. We nodded and stepped outside into day. There was a spring chill in the air, the last gasp of winter holding on to the hills. Vincente directed us to the trailhead where a small signpost was planted in the ground, which read “VVA Trail.” The Victor Vincente of America Trail. It sounded very grand and heavy with importance. It announced itself as some famous land feature might: Half Dome, El Capitan and Evolution Basin. The trail opposed the grandiose imagery its name evoked. Moss gently covered the stones and tree trunks surrounding us. It was just as he liked it, curving and hugging the terrain, moving with it.

We came to a footbridge he had built over a creek. It was sturdy and made out of slats of wood that had been painted garish colors of yellow, blue and red. The lumber was reclaimed from a group of Hare Krishnas that owned the land in the ’60s.

What transformed a timid boy racer into a prolific creative mind? A meandering chain of events precipitated this radical change, beginning when Hiltner went to Brazil for the Pan-American Games in 1963. Hiltner and his teammates stayed after an uneventful event.

Vincente remembered a special day they left the Pan-Am Village for a training ride: “On one of our first days out training from the Pan-Am Village, [Bob] Tetzlaff, [Tim] Kelly, about a group of six of us roadmen were out for a spin. I remember an intersection and there was a gal around the corner smoking a cigarette and we said hi to her, and she waves back—that’s all it took for me. I made a U-turn. That was my first wife, Naide.”

Their courtship consisted of free meals at the Pan-Am Village, where Naide worked as a switchboard operator. Despite Hiltner’s lack of Portuguese, they fell in love and he asked her to marry him. She said yes. Six months later the two returned to California, where Hiltner continued racing. That year, Hiltner won the U.S. National Road Race, which he regards as his greatest career accomplishment, and he was sent to San Sebastian, Spain, for the ’65 World Championships.

Vincente can’t remember San Sebastian: “I don’t think I finished.” Naide and Hiltner sold everything to live in Italy. They stayed outside of Florence, as Hiltner had as a budding road racer. Vincente prefaced the tale with a deep sigh. “That was the winter that the Arno overflowed its banks and did a lot of damage in Florence. The water invaded basements and historical archives. Did a lot of damage … Naide and I were living just a few miles outside Florence. Just to get into Florence was dangerous because you’d drive through miles of water. It was completely upsetting, so we just decided to go to Brazil instead of braving the winter.”

Without realizing it, the return to Brazil would lead Hiltner into the major doldrums of his adult life, and eventually, the collapse of his marriage. The two took a cruise liner to Brazil and Hiltner signed up with a local racing team. He struggled, was dropped and was left staring down the barrel of an existence outside of bike racing. Naide’s parents got him a job at one of the largest publishing houses in Brazil.

“I had a job. A real job. For three years straight,” Vincente remembered disbelievingly.

The loss of bike riding left Hiltner adrift. That changed when he and Naide encountered a pair of Mormon missionaries on the streets of Sao Paulo, and the couple ended up converting. This was hard to believe—Hiltner, or Vincente, a Mormon at one time? He quickly explained what he found so compelling.

“Well for one thing, if you followed that straight path and you do everything they tell you to and you learn everything that is learnable, eventually, sometime within eternity you can become a god.” He laughed heartily and continued. “Some kind of god, whether it’s the God or an assistant god, I don’t really know, but you could have powers of creation and decision making. So that was a part of it. I guess the organization itself was attractive.”

His time as a Mormon came full circle when he volunteered as a missionary. “I personally baptized four people. By that time I was an elder; you have to be an elder to carry out that function. So that’s part of your steps to becoming a god, eventually,” explained Vincente with a wry smile. “It was good for me in some ways, and it was deadly in others.”

Vincente tithed 10 percent of his earnings at the publishing house to the church. Naide always resented this, because well into their marriage, and in a home for more than a year, the couple could not even afford livingroom furniture. “The church in that way was sort of destructive to our marriage. But for me more personally, it gave me kind of an organization in my life.”

In the last year of their marriage, Hiltner and Naide had a child. Ultimately, they could not assuage his restlessness. All the life had gone out of the marriage, and he wanted to go back to California. The end of their marriage was the beginning of an immensely creative time period for Hiltner, and soon for Vincente. The idea of human-powered vehicles had come to him in Brazil— recumbent bikes encased in a fairing. Before that, though, Hiltner was occasionally struck with creative urges, like when he once did a watercolor painting in the offseason in Italy.

His homecoming to California in 1971 fell against the backdrop of a fizzling hippie movement. He dabbled in psychedelic drugs and marijuana, loved freely and created new things prolifically. “I did open up creatively during that period when I wasn’t racing. I’d always had a creative drive but had always put it on the back burner because of racing,” he said.

First, Hiltner built his human-powered vehicle. He was shocked to discover that others had the same idea and they were racing. He recalled steering problems during once race that led to speed wobbles and a crash into the spectators. Abandoning that, he started designing and fabricating clothes. He made androgynous designs that used sparkling or sheened textiles. Some used wizard-like sleeves, long skirts and monochromatic tie-dye. Eventually, he developed his signature-style overalls that frequently used vivid colors and unusual prints. They seemed to be the most practical outfit for a man inextricably tangled in his love for cycling.

He tried a racing comeback but had lost everything in Brazil. “I thought I would be a few seconds behind my best times up all of the climbs, but I wasn’t. I was minutes slower.” Still, his amazing endurance remained, so he hatched the idea of the double transcontinental record. Hiltner rode from Santa Monica, California, to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and back in 36 days and eight hours, establishing the double transcontinental record. He had a support crew that began with four men but dwindled to two. One decided to take a job in New York, while the other was kicked out when he stole the support car to go visit his family in Nebraska. He made a run for the car when the group had stopped to picnic on a watermelon. The highway patrol had to chase him down.

After long, contemplative days in the saddle, the name Victor began repeating in Hiltner’s mind, and when the ride was over, Mike Hiltner decided to change his name to mark his achievement. That is when he officially became Victor Vincente of America.

In 1979, Vincente made his big discovery. He remembers the moment very clearly. “I was on my bike one day, coming down a canyon road from Mulholland down to the San Fernando Valley, lots of fancy homes up there. I was heading home in the valley, I was going down this paved road, and then the pavement stopped and I was on a dirt stretch of sand and rocks and I got a flat tire. I liked that dirt stretch. The dirt impressed me so much.”

The creative engine began to run hot. “So right after that I figured, well, I don’t want a flat tire riding on dirt. I figured, well, if I put on heavier tires, I can easily do it.”

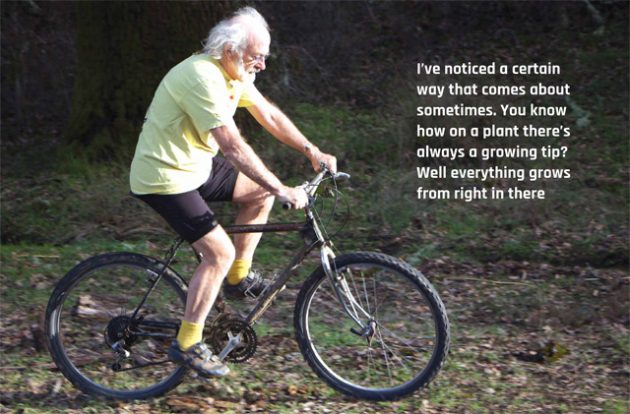

It began as a practical solution but grew into something else entirely. As we stood along the VVA trail, he took a California bay laurel in hand. “I’ve noticed a certain way that comes about sometimes. You know how on a plant there’s always a growing tip? Well everything grows from right in there. That’s the way I feel about creative ideas, it just sort of comes out. It sort of grows. So I usually find if I just let that happen, anything can grow.”

From there, Vincente developed the Topanga! frame. Topanga! used 20-inch BMX wheels with BMX tires, fitted into what was essentially a road frame. As soon as he had a machine, Vincente began frequenting the Santa Monica Mountains, discovering a network of fire roads he had no idea existed. He routinely found tire tracks that were his own and no one else’s.

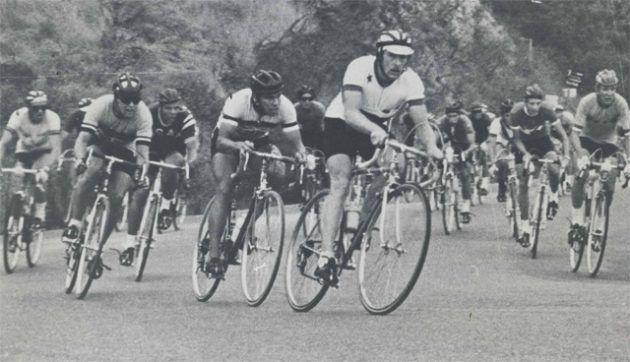

He soon began to hear murmurs of a dirt-riding group in Northern California, about whom he knew little. Bringing more people into the fold of dirt riding proved challenging. Vincente’s solution was to create dirt-riding races, most famously, Puerco!, as advertised in his Topanga Rider’s Bulletin in his own trippy typeface, West World. The races Vincente began to put on were not aimed at establishing a pecking order in the world of dirt per se but to find who else even existed in the world of dirt.

For his first race, a motley crew arrived from Northern California in a double-decker bus. Vincente soon found they were the Northern Californians he had heard of. “Gary Fisher won the race, Charlie Kelly was there, Joe Breeze was second place, then Wende Cragg and Denise Caramagno. They took away the prizes. Most of the prize list!”

Racing aside, Vincente’s primary love of dirt-road riding, or mountain biking as it was quickly dubbed, lay not in racing, but in the wild, in nature, the communion that was possible. “It’s not so much the feeling of the surface, but then there’s bushes right alongside the road, even on a mountain road when it’s paved—I don’t know, it just seems like there’s the road and then there’s wilderness, which seems almost alien. Not much interest in getting into the bushes. But on a dirt road, the bushes are right there, maybe there’s wildflowers, you can stop right there, there’s no traffic, you can leave your bike in the middle of the road, maybe look at the stones, the stones you’ve been riding over or the boulders on the side of the road. It’s more like you’re in the world.”

Vincente was also crafting electronic jewelry, a concept ahead of its time, perhaps too far. He was inspired by gazing at stoplights at night. Vincente’s first electronic jewelry used mercury switches, which were little glass capsules half-filled with mercury. He installed them in wiring boxes with holes drilled out for small incandescent lights that were covered with taillight plastic to emit different colors. The wiring box was worn as a pendant, and whenever it moved the mercury in the switch would splash and intermittently complete the circuit, flashing the lights. Vincente’s design continued to evolve, and he began using lines of LED lights to flash in different patterns. Despite their gradual sophistication, they were hard to sell for $300 apiece.

After years of honing his mountain bike frames, particularly his VVA 26-inch Semi- Custom Dirt Road Bicycle, which he showed us before our walk on the VVA Trail, Vincente moved on to a more permanent art form: coin making.

“Around ’88. This was another one of those instances where I dreamed something up and just had to make it happen. As a legacy and as a medium, [a coin is] more enduring than fabric. Since my teenage years I always enjoyed coin collecting and I had handfuls of favorite coins and I just realized I can make artwork and stamp it in metal and people could hoard it and keep it in a museum.” He laughed. “As with many other dreams I’ve had, inventions I’ve come up with, dirt road bicycles is one, coins another, I dream them up and they’re something new to me. For me it was an independent invention.”

Vincente raises an important question: “Does it matter who was first if you’re creating something for you the first time? From my point of view it’s just a new thing with me. It was just my child, my baby,” Vincente explained.

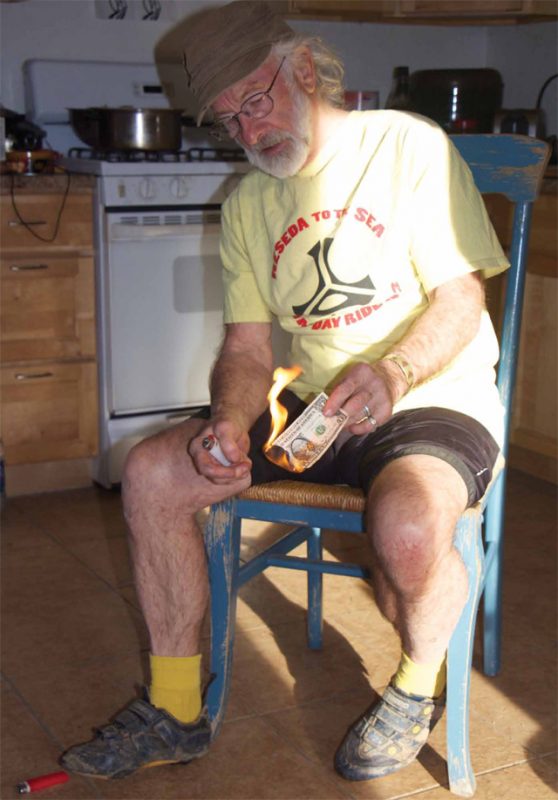

We reached the end of VVA Trail. The low sun cast long shadows from the 100-yearold walnut trees that surround his dwelling. He threw his leg over his VVA 26-inch Semi- Custom and rode around, the intrinsic delight beaming from him. Really loosened up, he asked, “You guys wanna burn some money?”

We went inside, and Vincente took a lighter to a dollar bill. “I do this when I become too preoccupied with material ambitions.”

For a man who at times seems to be at a crossroads in age, whose body has begun to fail him in disturbing ways for a lifelong bike rider, the gleam of intellectual glee burns brightly. He now considers bike riding a waste of time and would rather work on his book or absorb others’ creative output.

“Having been perfectly healthy for a long time, just to see the body start to go downhill is hard. Go downhill fast. I like that phrase too. I’m going downhill fast now!” And when Victor Vincente of America does leave the party, it will be going downhill. Fast.