Blast From the Past: Spine Owner’s Manual

Originally posted on April 28, 2016 at 7:00 am

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Dirt Rag Issue #142, published in May 2009. Words by David Alden-St. Pierre, MS, PA-C. Medical illustrations by Molly Thompson of Thompson Medical Illustrations.

There’s nothing like an epic day in the saddle: a few hours of riding, burning lungs, tired muscles, and for some riders, an aching neck and back.

Being hunched over with your head up can start to be uncomfortable after a few minutes; adding the demands of pedaling, pulling, and absorbing bumps, drops and dips can just make matters worse.

According to Todd Buckley, doctor of chiropractic, mountain biker, elite marathoner and co-owner of BioMechanix of New England (a bike fitting and gait analysis company), cyclists do lots of things to increase the stress and forces acting on the spine.

To learn more about these forces, and what you can do to help eliminate or reduce back and neck pain, let’s learn more about the anatomy of the spine.

Spine 101

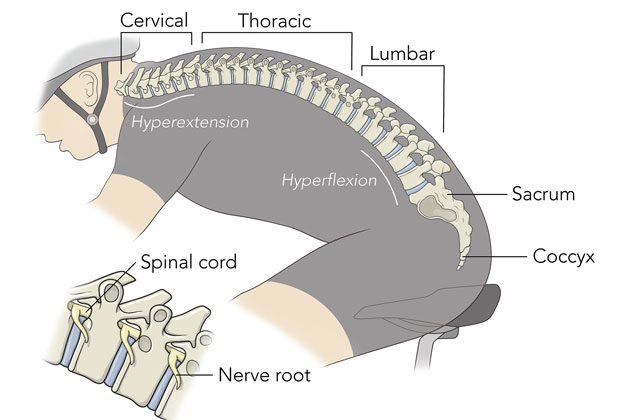

The spinal column, according to the “Manual of Structural Kinesiology,” is “the most complex part of the human body other than the brain and the central nervous system,” and no one argues with the “Manual of Structural Kinesiology.” The spinal column includes 24 vertebrae that articulate (have the ability to move against each other) and nine vertebrae that are fused together (coccyx and sacrum). They are all stacked up on top of each other with a thick, weight-bearing portion and a hollow portion that lines up for the spinal cord to go through. When viewed from the side, the spinal column should have a subtle but distinct “S” shape to it, and when viewed from the back, the spine should be straight. Between each vertebra is a disc designed to add cushioning and support to the spinal column. The best way to envision these discs is as jelly donuts, with a very soft inner area (nucleus pulposus—mmmmm, the jelly) held together with an outer coating (annulus fibrosus).

The first seven vertebrae are known as the cervical vertebrae, and your head attaches to the top vertebra, designated C1. The next 12, the thoracic vertebrae, have small non-articulating joints that join up with your ribs. Below the thoracic vertebrae, the lumbar vertebrae include the last five vertebrae that can articulate. Lumbar vertebrae are the largest, as they have to support the most weight. They are also usually the first to become injured because they are under stress, and most people do not strengthen their core muscles enough (including the author). The fused sacrum vertebrae join with the pelvis, and the coccyx (tail bone) finishes the whole thing up as far as the bones go.

Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves extend outward to send and receive messages to and from the rest of the body and the brain. Any damage, pressure or other injury to these nerves can be trouble. Aside from the nerves, plenty of other soft tissue plays an important role in neck and back health, including the discs mentioned earlier, ligaments and many muscles—some small and others quite large.

Standing straight, your back and neck are in the extended position. Bend forward and you are flexed, bend backward and you are hyperextended. If you put your left foot in and shake it all about, you’re in the hokey pokey position.

Oh My Aching…

Aside from actual trauma to the neck and back, most common cycling-related problems can be attributed to poor conditioning or poor fit. For example, “while riding, cyclists tend to hyperextend the pelvic/spine angle,” says Buckley, “which results in an increase in tensile forces acting on the spine.” He adds that an incorrect seat angle can be at the root of that problem. Additionally, handlebars that are too low or too far forward will force the rider to hyper-extend his or her neck in order to see down the trail. Considering that the average human head weighs about 8-12 pounds (not including helmet, helmet cam and thermonuclear protective sunglasses), that’s an enormous strain on muscles that were originally designed to simply hold the head in its correct position when you are standing upright. Maintaining this somewhat awkward position, or any position on the bike, is made even more difficult by the same terrain that we are out there to enjoy: rocks, ruts, roots, drops, climbs and jumps.

It is believed that suspension can help many riders with neck and back pain, and some doctors are learning this too. In an article by Robert Kronisch, M.D., in The Physician and SportsMedicine, both suspension and proper bike fit are recommended to help alleviate pain. The article also goes on to discuss proper fitting, but proper fitting means different things for different people, so generic recommendations are almost impossible to make.

Some riders might be naturally flexible enough to handle a low and tucked position, but may need stretching and strengthening exercises to reduce or eliminate pain. Other riders might simply be unable to assume a low position and they may need to look at a shorter stem, riser bars or both. Obviously, handling characteristics of the bike change when your position is changed, so a compromise might have to be found. In general, a more upright position has less strain on the neck and back.

Over the years, treatment for back pain has migrated from rest to more active recovery with light exercise. The best way to reduce or eliminate pain, says Buckley, is to “avoid situations in which the back is placed under great strain.” Since for most of us, that would mean not riding, we all know that’s not really an option. Buckley then recommends strengthening exercises such as pelvic tilts, partial sit-ups, bridging exercises, prone exercises and Swiss ball exercises. Just plain walking has also been found to be helpful in loosening tight muscles in the lower back. And when it comes to the eternal debate of heat or ice, there doesn’t appear to be a right or wrong answer—use what feels good for you. I use both—a heating pad on the back and an ice cold stout in my hand.

Other aspects of your life, including the amount of time you spend sitting in front of a computer, TV or steering wheel; posture while sitting or standing; and even your bed can all have a significant effect on your back as well. Neck and back pain may not be caused by the bike at all.

Getting Help

So how do you know when you’re just sore from a long ride, or you have a problem you need to have checked out?

Back pain associated with any of the following requires prompt evaluation: fever, weakness/numbness/tingling, bowel or bladder problems, a history of cancer, or night sweats. “Persistent, nagging discomfort is another warning sign, and any type of trauma, weakness, and/or radiation of pain down the leg could be indication of a disk injury,” adds Buckley. In the absence of these symptoms, most back and neck pain is simply muscular in nature and can be treated fairly conservatively.

What kind of health care provider should you see? I don’t want this to become a forum for the pros and cons of different forms of treatment, but many allopathic (traditional) doctors don’t approve of the care that chiropractors provide. To this, I simply offer one of my experiences. I had some back pain and I knew it was from a tight muscle pulling me out of alignment. Had I gone the allopathic route, I would have probably been prescribed some anti-inflammatory medications and stretching exercises, and told to wait a couple of weeks to see how it felt. On the other hand, after one visit to a chiropractor I was feeling 99 percent better.

Whichever way you go, if you are having chronic pain, get it checked out. A good physical therapist, trainer or coach might be helpful in evaluating your bike fit and in stretching and strengthening your back. Also remember to look for possible non-bike related causes. Simple mechanical back pain most often has a simple cause, be it poor fit or weak core muscles, and can often be solved without long-term problems. Research shows that no matter what type of intervention you receive (spinal manipulation with a chiropractor, physical therapy, a course of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen), the vast majority of people get better when there is an acute episode of back pain. The key lies in reducing the factors that might make that happen again, and sadly, that might mean doing some core exercises.

Keep reading

We’ve published a lot of stuff in 26 years of Dirt Rag. Find all our Blast From the Past stories here.