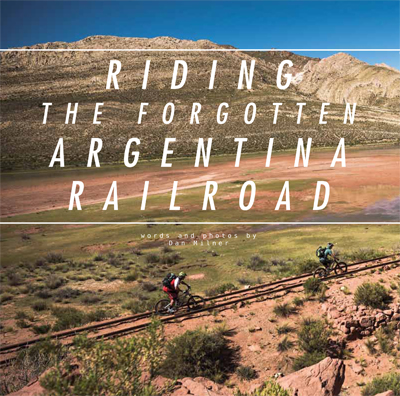

Feature: Riding the forgotten Argentina Railroad

Originally posted on November 4, 2015 at 12:00 pmWords and photos by Dan Milner

This story originally appeared in Issue #183

“It’s the most shitty looking, crappiest trail I have ever seen,” says Hans Rey, not mincing his words. We’re tired, hungry and cold and have found ourselves passing the night in the one-horse Argentinean border town of La Quiaca—a town that seems to exist solely to encourage travelers to leave. Looking north, a concrete bridge spans a trickle of grubby water that separates Argentina from Bolivia, and to the south, extending as far as the eye can see across a desert landscape, is the trail along which we’re about to mountain bike. Or perhaps “trail” is too generous a term for a 100-year-old disused railway line.

“It’s the most shitty looking, crappiest trail I have ever seen,” says Hans Rey, not mincing his words. We’re tired, hungry and cold and have found ourselves passing the night in the one-horse Argentinean border town of La Quiaca—a town that seems to exist solely to encourage travelers to leave. Looking north, a concrete bridge spans a trickle of grubby water that separates Argentina from Bolivia, and to the south, extending as far as the eye can see across a desert landscape, is the trail along which we’re about to mountain bike. Or perhaps “trail” is too generous a term for a 100-year-old disused railway line.

Completed in 1912 by British engineers, the meter-gauge line that is to host our two-day ride was once the quickest and safest way to travel through the arid and bandit-infested desert north. Subsequent economic depression, then privatization in the 1970s and finally abandonment in 1992, means the steam trains that once plied the Línea Belgrano Norte have long since disappeared. But the line itself remains: a straight, level track slicing through some of the world’s most impressive scenery.

It’s taken me six years to get to this point, having first laid eyes on this iron-railed remnant of industrial history during a previous bike trip here. During one of those seemingly regular moments of madness, I succumbed to the idea that to mountain bike along this old railway line might make an interesting interlude in my life. It would be a challenge, I reasoned, but no doubt strangely rewarding.

Traveling by bike means immersing yourself in your environment. It means seeing things that otherwise pass by too quickly from the seat of a bus. It means coming home with experiences and rewards that are not listed in the guidebook. And so the romantic notion of an adventure was spawned in the way they so often are: peering from the window of an air-conditioned rental as I sped along a silky smooth tarmac road.

Now, as we sit in a café chewing stale pastries and sipping on hot chocolates as part of the Argentinean afternoon-tea tradition, I’m a little hurt by Rey’s remark. Don’t get me wrong: I have no warmth for this grimy town or our $10 hotel, run by Argentina’s laziest proprietor. But the reason that I am here with fellow mountain bikers Rey, Tibor Simai, and Rob Summers is that the trip speaks to my sense of what makes a good adventure.

This railway is my baby. I’ve researched it, squinting at its faint form on Google Earth and missing last calls at the local pub while at home pondering logistics and viability. But I realize there is some truth about Rey’s comment that is striking a chord in me, too. The last bus we took paralleled the railway for 25 miles, allowing us a preview of what we’re embarking on and, while adventure is guaranteed, the actual riding didn’t look too promising. Swallowed up by drifts of sand, overgrown by sagebrush, and teetering over a dozen broken bridges, my chosen mountain bike trail is no weekend ride in the Surrey hills. I guess it’s why no one has tried to ride it before.

The sun is low, but I can already feel its savage bite as we start our escapade the next morning. Over two days we’ll attempt to ride as much of the railway as we can, starting at Abra Pampa and finishing among the cobbled streets of Humahuaca, 60 miles to the south. A decade living near the Bristol and Bath commuter bike path in the U.K. has familiarized me with the easygoing gradients of railway lines converted to bike thoroughfares. Typically they produce the kind of inclines that let you mash gears in never-ending sprints, working on cardiovascular targets while dodging potential muggings.

But this time it’s the altitude that does the mugging. In Abra Pampa’s corner shop we wade through a sea of bowler-hat-wearing indigenous women to fill our backpacks with bananas and water before pedaling to the railway line and straight into a 12-mile-long climb. I’m right about the easy gradient, but faced with an incessant headwind and the lung crunch of riding at 11,154 feet, this initial gentle-but-unrelenting climb proves harder than any of us envisaged. A month of regular turbo-trainer sessions in my garage seems to have done little to help right now, and my legs feel heavy and useless. Repeatedly we’re forced off our bikes to climb over barbed-wire fences that now pay little respect to the railway engineers’ noble notion of cutting an unimpeded course across the landscape. Herds of llamas and guanaco stand their ground, unaccustomed to being confronted by bikers, and we’re forced off the line to roll down the embankment only to have to haul ourselves back up again to continue.

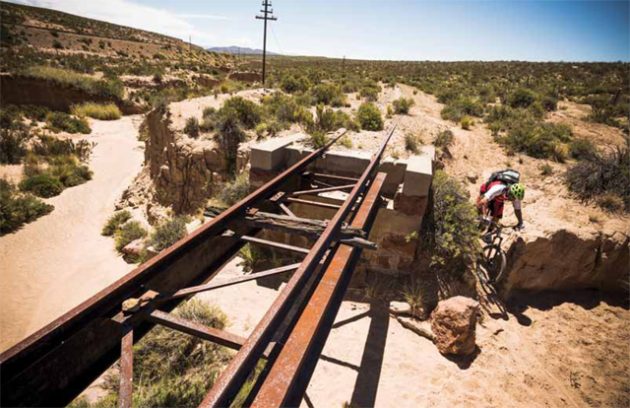

By midmorning we’re feeling the full ferocity of the sun. There is no shade here, and in three days’ time we’ll all be shedding skin like serpents at a clothes swap. The vast altiplano we’re traversing is crisscrossed by dozens of small, dry creek beds, each spanned by a railway bridge that hasn’t seen maintenance for 20-plus years. Some are intact, their wooden sleeper slabs still evenly spaced about 30 centimeters apart, allowing us to ride across them if we carry momentum, but some wield gaping holes where sleepers have disappeared. Others yet have been reduced to nothing more than a twisted tangle of ironwork. The approach of every bridge brings a tingle of apprehension, and crossing them becomes a game of calculations and nerves.

We’re only 5 miles out of town, but already the feeling of space is immense. Above us, a vast blue sky reaches down to touch the rugged peaks of the Andes. The line’s 3-foot gauge gives us just enough space to maneuver between the rails, and we swerve around the clumps of prickly brush that thrust unsystematically from the earth and hop over randomly projecting sleepers. With a little momentum, picking a line through the undergrowth begins to deliver a rhythmic flow to the riding, like railing good singletrack.

It becomes apparent that, left untended, the railway is slowly being reabsorbed into the environment by nature. Gopher burrows acne the ground and adjacent telegraph poles, relieved of their messaging duties, have relaxed their guard. Their broken wires hang limp and their Bakelite fixtures have become platforms for tangled weaverbird nests.

Thankfully for us, the wooden sleepers have long since become buried under drifting sand, now baked hard under decades of unrelenting sun, making the riding easier. In places the sleepers have disappeared completely, seized as hallowed building materials by locals lacking trees or a Home Depot. In the absence of such ground anchors, here the rails have become bent and contorted by the desert heat.

We’re parched and burnt by the time we reach our first day’s finish, Tres Cruces, a small village that is little more than a jumping-off stop for the nearby uranium mine. Accommodations—or, more accurately, lack thereof—have been a big challenge in planning this adventure, with few villages positioned along the line. Some towns in the area, such as Humahuaca or Tilcara, have become tourism hot spots and accommodations are guaranteed, but at tiny Tres Cruces we’re taking a gamble. We lose.

Locals point us to the one hotel in the village, but clearly it hasn’t been open for years. Opting to travel light without camping gear, and now faced with nighttime temperatures below 30 degrees, we have little option but to jump on a bus back to Abra Pampa for the night and return to Tres Cruces at dawn to continue our ride. It’s a frustrating turn of events and, in hindsight maybe throwing in a sleeping bag each would have been wise. Then we’d have been able to entertain our grandkids with stories of how we slept out in an old retired railway wagon in a ghost town of a village near a uranium mine.

Nothing wakes you up quite like a 7 a.m. ride in the back of a pickup truck speeding across a desert plateau at 11,150 feet. Still wearing down jackets, we’re delivered back at Tres Cruces’ abandoned station early enough to get a jump on the heat of the day. We pedal out beneath towering water tanks that once flooded the boilers of steam engines and past rusting signaling pylons. It’s like riding through a museum.

We’re in good spirits, helped by the start of a gentle descent into the Río Grande valley. We skip across bridges and up the pace to cross lengths of railway left suspended in mid-air by the undercutting action of the adjacent river. Our progress is humbled by a landscape of colorful rock layers, each twisted and thrown into disarray by unfathomable geological forces. We pass a remote hilltop cemetery at 12,500 feet, its iron crosses decorated with rosary beads, ribbons, and cheap plastic posies. Scattered animal bones bleached white by the sun and the desiccating corpse of a llama serve to remind us of the possibilities should something go wrong out here. “But what can?” we ask ourselves. After all, we’re just riding along an old railway line, the shortest and easiest way from point A to point B.

And then the bridges loom into view. Each is perhaps 200 feet long and suspended 100 feet above a chocolate-colored Río Grande, and there are two to cross. Even encountered separately, each could be a contender for the most mentally challenging part of our two-day adventure. Too long and with too many gaping holes due to missing sleepers to try to ride across, we’ll be walking these. But like their smaller brethren we’ve already negotiated, the bridges have no walkway, no handrails—only the rails and wooden sleepers and gaps between them, lots of gaps.

I gingerly step onto the first bridge, trusting the decrepit ironwork while cursing the blustery cross-wind that has arrived to add to the drama. Never good with heights, I fight the urge to peer down into the void that beckons between each sleeper, hoping my cleated bike shoes will give me the sure-footedness I need to stay upright. An attempt to wheel my bike quickly fails, its front tire dropping into the first broken gap and the rest of the bike nearly following into the abyss. My impoverished railway-bridge-crossing skills nearly cost me my bike. I wrench it out and haul it above the rails, wondering how or where you might be able to practice and hone such skills before coming on such trips.

By the time I reach the “safe” end of the second bridge, my mouth is dry, my legs are wobbling and my forearm is cramping from the vice-like grip I’ve exerted on my bike. But as I slump down onto the railway siding and regain control over my breathing, I realize the worst is behind me. Even from behind the windscreen of my rental car six years earlier, I knew these two bridges would present the biggest challenge should I come back to ride this railway line. With no idea of how safe they were, I’d even entertained thoughts of lugging an inflatable pack-raft with us to use to cross the river instead.

I watch as my fellow mountain bikers make the same crossing behind me, each caught up in his own mix of adrenaline, focus and sense of accomplishment. “For every tough mountain bike trail, there is always one harder,” I think, and for every remote adventure, there is always another just as unique. I realize that while the adrenaline rush of riding somewhere new, somewhere no one has ridden before, comes thick and fast, that buzz is ephemeral. For me, the lasting resonance of adventure is in what you learn about yourself and in those who share your experiences.

I swing my leg back over my bike. Humahuaca is still another 20 miles away—20 miles along one of the “crappiest” trails I have ever ridden. We set off again, not knowing what lies around the corner, but knowing that so far it has become fun. I look back. Even Rey is smiling.

Never miss an adventure like this. Subscribe to Dirt Rag today and sign up for our email newsletter to get fresh content delivered to your inbox every Tuesday!