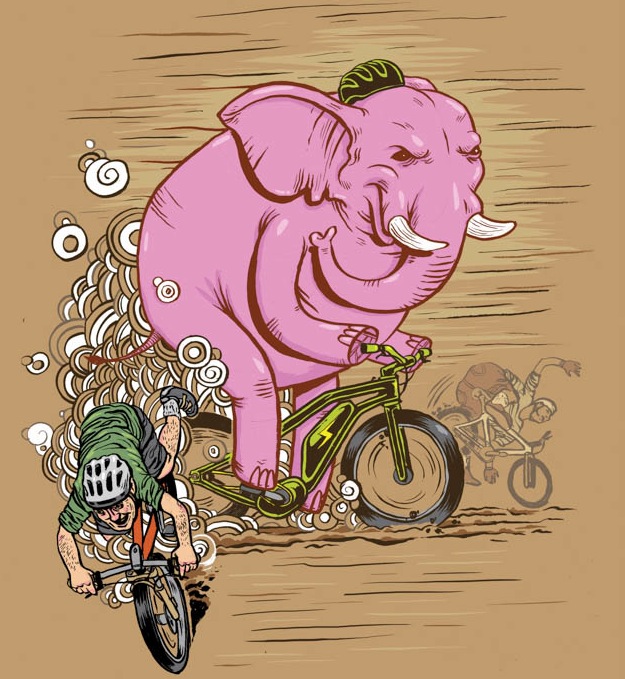

Elephant In The Room: The Great E-Bike Controversy

Originally posted on January 22, 2015 at 6:27 am

By Jeff Lockwood. Ilustrations by Stephen Haynes

One should never dwell too deeply on any polarizing statement frivolously tapped out in the comments section of any online article or posting. The stunning language, poorly argued opinions, hilarious misspellings and ill-informed “facts” expressed by virtually anonymous people can boil the blood of even the most level-headed, stable person. This is especially true with hot-button topics such as the emergence of electric-assist mountain bikes.

For example, read this Facebook comment posted in regards to a Dirt Rag mention of the Lapierre Overvolt electric-assist mountain bike:

The first one of these that I see on the local trails I’m taking out. See, you need to cull the heard of weaker less capable bikes (or ones that allow weaker and less capable people on the trails). Remember, it’s much more humane to cull the heard of early in the season than let some fat ass tourist run out of go-go 10 miles from the trail head.

A lot of the fear, concerns and opinions rest on the misconception that people will be out tearing up the local trails on a slimmed-down version of a motorcycle—a vehicle lacking any human effort to propel it.

It’s safe to assume that no bicycle manufacturer, advocacy organization, land manager, professional athlete or casual rider will ever want to see Harley-Davidson’s recently announced electric motorcycle ripping around Kingdom Trails in Vermont, Gooseberry Mesa in Utah or your local ribbon of buff singletrack. What we’re investigating in this article are bicycles: machines that are moved by the use of actual leg muscles, yet also feature a small electric motor to augment its forward movement.

There are at least a few different technologies from various manufacturers that use a motor somehow engaged by the rider to assist with movement of the bike. That means real effort is still required to turn the pedals. Electric-assist bicycles do not move forward by themselves.

For simplification, clarification and efficiency with regard to this topic, we’ll generalize all of this technology and collectively refer to it as “electric-assist.”

Bicycles sporting some form of electric enhancement have been around for a long time. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Lee Iacocca, once the head of Chrysler and Ford, led one of the first companies to bring a serious electric bike to market, branded as “eBike.” Iacocca brought a high level of business acumen, lots of money and a certain level of legitimacy to the electric-bicycle concept. While eBike eventually folded, it did prove that the concept was ready for the big time.

Today, electric-assist bicycle technology comes in a few flavors. There are versions like the BionX system, which is an aftermarket product that retrofits any current bike by adding a battery to the frame and an electric motor in the hub of the rear wheel. Currie Technologies, owned by the Dutch bicycle mega-company Accell Group, also offers systems that can be retrofitted to current standard bicycles while also offering more integrated solutions to the likes of Haibike. Bosch, the company that provides the electrical system for many automobiles, now licenses a very slick and rather aesthetically unobtrusive electric system based around the bottom bracket. And, clinging to the inherent independent nature of mountain biking, you also have smaller start-ups delivering custom electric-assist technology and complete bikes, such as Kranked, based in British Columbia.

Personal Concerns

On a very basic level, some riders feel personally threatened by the mere existence of a bicycle equipped with any sort of motor. Some mountain bikers seem to have a potent combination of delicate egos and well-trained bodies. While struggling up a difficult climb, seeing a less-fit person breeze by using anything other than oxygen, muscle and determination will leave many riders seeing red and dismissing the offending rider as well as whatever new technology is carrying him or her up the hill.

Rob Kaplan is vice president of sales and marketing for Currie Technologies. It’s his job to be aware of the criticisms of the electric- assist mountain bike and to debunk the myths. One of the most audible knocks against the concept is that “it’s cheating because it’s an electric motorcycle.” Kaplan counters that thought by reasoning, “It is not cheating, as these are ‘assist.’ You must pedal, and pedal hard at times. It simply amplifies your output, allowing you to do more than you otherwise could.”

While so many of us cyclists love new gadgets and concepts to improve our ride experience, the dirty truth is that many of us cling to tradition and remain very stubborn when it comes to emerging technologies on or around the bicycle.

Gary Fisher is one of the forefathers of the mountain bike and a proponent of many technologies that were once considered disruptive, but are now taken for granted on our bikes. Fisher fought early and fought strongly for the 29-inch mountain bike wheel concept and faced lots of resistance. He said, “There would be 50 mountain bikes this guy would have in his shop. Two of them would be 29ers. They looked like orphans. ‘Who’s going to buy that?’” He also ran into friction when he tried to spec suspension forks on his bikes. “I was the first maker to put it [a suspension fork] on a [production] bike, and all my internal sales guys thought I was crazy, thought I was stupid,” Fisher remembers.

It’s obvious that we’re seeing the same kinds of battles today when it comes to electric-assist mountain bikes, and Fisher recognizes that these bikes are very disruptive to the status quo of mountain biking. Yet he sees electric-assist mountain bikes as inevitable—and a positive evolution. “People will try it and say they had too much fun: ‘I’m out of shape, I wanted to go do the high altitude.’ We’ve got hardcore stuff here in the States, man. We have high altitude, baking-hot weather. That bike is gonna make everything easy,” Fisher predicts. You go out with a group of people and three of them that aren’t normally so fast are on electric bikes. That’s cool. Believe me. This stuff is gonna come.”

Fisher’s statement touches on an important point: inclusion. And it’s something that bicycle companies are eager to capitalize on. We all ride at different paces and enjoy mountain biking for different reasons. Yet we have to admit that mountain bike riding requires significant physical commitments, which can be prohibitive to a potentially huge market.

The fact is that a lot of people don’t ride mountain bikes because getting themselves and the bikes up and over some hills and other obstacles is just too difficult.

The fact is that a lot of people don’t ride mountain bikes because getting themselves and the bikes up and over some hills and other obstacles is just too difficult. Sure, a whole category of our beloved sport sees riders being toted up a hill in the back of a pickup truck or on a ski lift for the sole purpose of bombing down the mountain. But most mountain bikers—and potential mountain bikers—also enjoy the simpler act of riding trails, exploring the woods and making a day out of a bike ride. The argument goes that if you help alleviate some of the physical challenges of mountain biking, the sport will “see more butts on bikes.”

Bjørn Enga, owner of Kranked, sees the writing on the wall. “Everyone that has tried my electric bikes has loved the experience; [it] blew their minds. The market is so much bigger than the bike market caters to at the present moment. The number of people on this planet that can actually ride their bike up a hill, let alone a mountain, is tiny.”

It’s a safe argument to make that the spirit of mountain bike technology lies with the tinkerers, the visionaries, and those willing to take risks. That’s how mountain biking was “invented,” that’s why the 29-inch wheel is so ubiquitous now and that’s why we’re starting to see electric-assist mountain bikes. While much mountain bike innovation might come from these independent minds, it’s not exclusively their domain.

“Electric-assist mountain bikes are turning on new riders and adding to the growth of cycling. It will be another entry point or maturation point for the overall cycling market,” says Travis Ott, Trek global mountain bike brand manager. Trek currently produces three models of electric- assist mountain bikes, which are powered by the Bosch system. While the hardtail Powerfly+ is currently available only in Europe, Trek is carefully watching the U.S. market for the moment when it makes the most sense to release an electric-assist mountain bike stateside. “If it gets more people on bikes, enjoying off-road riding, extending their ability to ride, getting them back into riding, enabling them to go further, riding with buddies they wouldn’t otherwise be, whatever, I’m all for it,” says Ott. “The more people in the sport, the better.”

Electric-assist bikes in a more urban setting are definitely starting to catch on in the United States. But Europeans have embraced electric- assist bicycles for several years. Mike Defresne publishes an electric- bicycle magazine in Belgium. He also publishes O2 Bikers, the largest mountain bike magazine in the country. Defresne explains that cycling in Europe is a very social activity and that electric-assist mountain bikes allow people to go farther and spend more time with their friends.

“Organized recreational rides are very popular, with distances going from 10 to 80 kilometers [6 to 50 miles],” he explains. “People like to do that, and with electric-assist mountain bikes, they can do longer distances and [ride] later in their lifetime. Now you see people that are 50 years old and beyond buying electric-assist mountain bikes because they don’t have the condition anymore to suffer on the bike. Because biking is a social thing, electric-assist mountain bikes will help them biking with their friends.”

Defresne is quick to point out, however, that electric-assist mountain biking in Europe is not quite an electrical utopia. “It’s a little like bringing back motorbikes into the woods, which is not good for our image,” he admits. “Plus, our market is performance oriented, so bikers are still embarrassed to admit they need electric assistance.”

While some people may perceive electric-assist mountain bikes to be a threat or an embarrassment, more and more people are also seeing them as opportunities.

Todd Gallaher was a cycle courier in Seattle and a professional mountain bike racer. Bicycles provided his livelihood. While leading out a teammate during a local criterium road race, Gallaher hit the deck. Hard. In addition to several broken bones and abrasions, he suffered a fracture on the distal end of his femur and a broken patella. He had to keep working, and putting some electric power on his mountain bike allowed him to work, rehab the injuries and recapture some of the fun of riding. “The add-on power plant to my race mountain bike let me fly along with my right foot clipped in and the broken leg on a platform pedal,” he says.

Environmental Concerns

While lots of sensitive (and vocal) mountain bikers may have their egos threatened by someone rolling past on an electric-assist mountain bike, most riders are more concerned with the potential impact that electric-assist mountain bikes will have on trails. Physics dictates that trails will deteriorate more quickly because electric-assist mountain bikes create more torque. More torque means wheels will turn with more force. More wheel force at the contact point with the soil negatively impacts the trails. And if the sport of mountain biking sees a sudden influx of riders like everyone is expecting, existing trails might not be able to handle more people. The situation is complicated by the fact that many new riders might not be up to date on their trail etiquette and rule following.

If [the trail] is made for mountain bikes with no motor assist, and people are using [electric-assist] on the trail, then I think it’s going to be bad for cycling in general.

Professional mountain bike racer and ardent trail advocate Mark Weir explains one of his concerns: “If it’s a green-sticker trail—a green sticker refers to California’s classification of allowing off-highway vehicles, motorized or not, to operate on public lands year-round— then electric-bike people are going to have to start doing trail work. But if [the trail] is made for mountain bikes with no motor assist, and people are using [electric-assist] on the trail, then I think it’s going to be bad for cycling in general.”

Currie Technologies has been in the electric-assist bicycle game since 1997, and Kaplan is keenly aware of the delicate ground upon which electric-assist mountain bikes tread. “I was in the thick of the trail-access issues in NorCal in the ’80s. I know that trail access is a fragile thing and that most mountain bikers do not take it for granted,” he says. Kaplan’s approach to land access and electric-assist bikes is a positive one. “This category can help get more participation in our activity and more participation means more demand for infrastructure and more political juice.”

Frank Maguire is a former IMBA regional manager and has built many miles of trails with his own hands. He doesn’t necessarily see a problem with the actual electric-assist mountain bike product. As an advocate of open space and sustainable trail-building, he’s more concerned with the higher number of trail users and their impact on existing trails and how to manage that situation: “[The problem is] not the users saying, ‘Oh, they shouldn’t be here.’ It’s more along the lines of, ‘Can we actually accommodate them? Can we say this is OK?’ Because we’re going to have more people in more places where maybe it wasn’t a big deal before. But now that there’s more people there, it’s going to be a problem.”

It’s interesting to note that IMBA is not specifically against electric-assist mountain bikes. Instead of creating heated resistance, IMBA, through a recently published white paper, essentially explains that the organization wants to ensure that mountain bikes and anything with a motor are classified separately. The white paper explains, “IMBA is an advocate for the interests of mountain biking and the development and maintenance of singletrack trails. IMBA objects to land-management practices and principles that address mountain biking and motorized uses as a single class.”

While that statement doesn’t support electric-assist mountain bikes, it certainly doesn’t dismiss them. Mark Eller, communications director for IMBA, further explains the organization’s position by stating, “Mountain biking is a human powered activity. Anything with a motor or power assist is considered a ‘motorized’ form of recreation…pedal-assist or not. We are not against motorized or pedal-assist technology, but they are inherently different experiences. There’s a non-motorized experience that people crave. A bicycle is a simple machine.”

To illustrate this point, Eller explains, “Paddling a canoe and getting around with an outboard motorboat are two different ways to enjoy being out on the water. While they differ significantly and are usually separated, they are able to get along.”

Going Forward

Aside from some vocal opponents of electric-assist mountain bikes, the consensus seems to be that these forms of mountain bikes are coming and their momentum can’t be stopped. Bicycle-industry insiders definitely get a twinkle in their eye when they see the financial possibilities that lie within the largely untapped market.

With an aging and increasingly overweight population in the United States that’s transcending most demographics, we’re going to see more people with the need and desire to get outside and be active. According to a 2012 study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) titled “Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among U.S. adults, 1999–2010,” 35.5 percent of adult men and 35.8 percent of adult women were classified as obese in 2010. Between 1980 and 2000, the Centers for Disease Control tells us, obesity rates in children and adults in the United States doubled, tripling among adolescents. With information like this, some sort of adaption to the concept of a mountain bike needs to at least be considered for mountain biking to remain relevant.

As such, IMBA concedes that ignoring the electric-assist mountain bike trend is a fool’s errand. Eller explains, “We are considering [electric-assist mountain bikes] at the 2014 IMBA World Summit because we have no business burying our heads in the sand by pretending electric mountain bikes don’t exist. It makes no sense to ignore the issue. We [mountain bikers] are born out of an innovative approach to technology, so we need to continue to look at how mountain bike technology will change.”

Exactly how to change the mind of the consumer is something that will be up to the marketing departments and other proponents of the concept. “Legitimacy happens when riders, journalists, opinion makers and the opinionated experience the technology and have an amazing experience. This experience makes them adopt the technology,” explains Enga. While it’s true that seeing (or riding) is believing in many cases, the question of how to get people to give it a chance is the real trick.

Poison Spider Bicycles in Moab, Utah, is one of the premier shops in one of the premier mountain biking locations in the world. With more than 40,000 people coming through the doors of the shop each year to rent bikes, it’s safe to say that Poison Spider can be considered highly influential in the mountain bike world. Bicycle companies often provide rental fleets to renowned shops like Poison Spider to market their latest bikes to the public.

Electric bikes will also get people into the backcountry that should not necessarily be doing it by bicycle…this will bring up issues of not being prepared, not having the proper clothing, food and water.

Getting electric-assist mountain bikes in a powerful shop like Poison Spider would surely tempt seasoned cyclists to consider buying and riding electric-assist bikes. However, Poison Spider is having none of it. Owner Scott Newton explains, “We already have access issues on certain trails, and we get categorized into the ‘no mechanized vehicles allowed’ classification,” he says. “If all of a sudden there are more electric bikes on trails that are built for mountain bikes, hiking, and horseback riding, it might ruin it for the non-motorized bikes.” The issue is compounded by the fact that the landscape around Moab can be extremely inhospitable to humans. “Electric bikes will also get people into the backcountry that should not necessarily be doing it by bicycle,” Newton adds. “This will bring up issues of not being prepared, not having the proper clothing, food and water.”

While Moab might not be the most welcoming place for people to demo electric-assist mountain bikes, private resorts could present the possibility of offering electric-assist rentals or demos. Ski resorts, which have special use permits with the U.S. Forest Service or other public-lands agencies, or situated on private land and have long been offering mountain bike programs during the summer to increase off- season revenues. If electric-assist mountain bikes were provided to the rental and demo fleets at these resorts, they could easily welcome a new generation of cycling enthusiasts.

Sara Burdon from Lapierre echoes the adage that riding is believing: “At the moment, we can’t make them fast enough. The key to sales is testing. At first, many people are skeptical. However, once they have tried them, lots of people change their mind. What’s astonishing is how many customers are coming over to electric bikes.”

For Ott, he feels a heavyweight personality or company can help push a trend into the marketplace. “Demand can be seeded many different ways,” he offers. “However, more often than not, it takes a big player to stick his or her neck out to really help things gain traction. With 29ers, it was Gary Fisher and Gary Fisher dealers who pushed 29ers for a decade before the market really caught on. With electric- assist mountain bikes, you’re starting to see those big players step in. And one of those players is Bosch, who’s helping to create a viable electric-assist drivetrain.”

Larry Pizzi, president of Currie Technologies, is fully aware of the impact, literal and figurative, that electric-assist mountain bikes can have on trails and access. “We [the electric-assist bicycle industry] certainly don’t want to do anything that would put trail access at risk and negate the great work that IMBA has done over the last few decades,” Pizzi says. “We are hoping that we can get IMBA’s help to promote electric-assist bikes and all of the places that electric- assist bikes can be legally used today, and then, as the category is better understood, begin to work on broader access in areas that make sense.”

Weir understands the passion, the politics, and the realities of the situation and that getting everyone to play along is a delicate job. “People are super passionate about losing where their spirit is,” he says. “But you can’t win with just force. You really gotta get in there and work it out with everyone so everyone’s happy.”

According to Gary Fisher, new technologies follow a roughly 10- year cycle before they’re commonly accepted. “It takes 10 years for just about everything. That front fork I was telling you about…it took 10 years,” he says. “We had a dual-suspension bike at the end of 1991, and that whole program didn’t sell until 2001 when Paola Pezzo won a World Cup on one. Took 10 years for carbon bikes. Ten years for titanium bikes. It’s all about the speed of the gray matter! Just relax and hit it right on time and you’re gonna hit the early adopters at the beginning.” He goes on to say, “There are going to be more people having fun…there are going to be more people buying our bikes! This whole sport is going to be bigger! I think it’s going to be great.”

Editor’s Note: The rapidly growing popularity of e-bikes on trails is ruffling a lot of feathers in the mountain bike community. In Dirt Rag #179 we took an in-depth look at the issue and received a lot of feedback. Here you’ll find the IMBA’s position on “motorized” bicycles. Dirt Rag magazine supports IMBA’s stance and believes electric-assist bikes should be limited to motorized vehicle trails only. As such, we currently won’t be testing any electric bikes off-road.