Blast From the Past: The Shaming of the True

Originally posted on March 12, 2015 at 14:36 pm

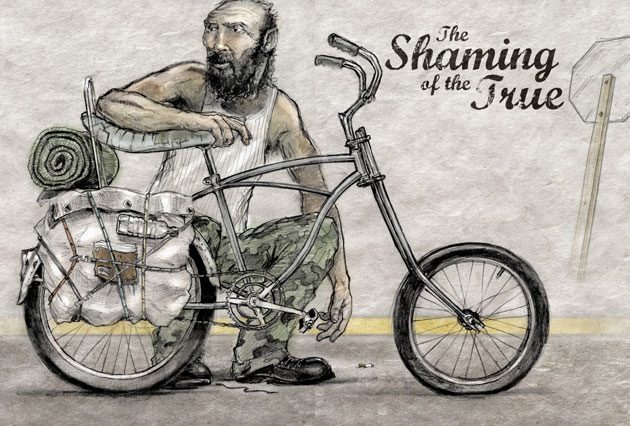

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in Dirt Rag Issue #122, published in July 2006. Words by Bill Ketzer. Art by Kevin Nierman.

“I find your lack of faith disturbing.”

– Darth Vader

This year sucked for riding. It wasn’t the weather. In fact, the pestilent, blistering hellfires of July and August the gods bequeathed led to absolutely fantastic trail conditions. No, instead my absence from the saddle was purely self-inflicted. One commitment led to another, and before long my demeanor smoked and withered like the once-green cubes of lawn in my neighborhood due to lack of rainfall. I have always been a workaholic, but not once had it ever kept me off the bike and held fast in the bittersweet arms of commerce, home ownership and marriage. Not until 2005.

Now, make no mistake. Marriage, like Metamucil, has its benefits. And there is nothing finer than actually having a driveway, especially after renting in Albany’s South End. We would have allowed my realtor to advise closure on a glacial cave on the Baffin Island interior so long as it had a blessed landing patch to call our own. But one day this year something happened.

Work had slowly evolved into a troublesome thing, even though the job is decent. I have an astute, fair and good-natured attorney for a boss who speaks with the same passion and introspection about prizefighting as she does constitutional law and state procurement issues. And the money’s not bad, but I could not shake the sneaky feeling that, if I woke up 20 years from now and all I’d done with my life was wear the suits, read the laws, go to the dentist, put ten percent of the paycheck into no-load mutual funds and buy driveway sealer, I would also then buy strong rope and do the thing all considerate suffering men do. Oh yes I would.

So, I began to assume other responsibilities, with an eye toward an eventual career change, but instead, I became more like a farmer collecting old engine parts to cope with the ridiculous price of harvest machinery. I freelanced for a local weekly, took up boxing, started up another band (hey, that’s always good for mental health), drummed in another, and stayed off the whiskey, hallucinogens and paint thinner. I also maintained two websites, handled all the band business, fixed broken faucets, carved out quality time with the wife, mowed the lawn, walked the dog, paid the bills and on and on.

Before I knew it, I only saw actual dirt on two wheels about five times this year, and my beloved daily commute to work ceased to exist. Big mistake. I even skipped the Pedro’s Festival for the first time since its inception. The Subaru Forester, once a lonely and overpriced dinosaur in my beloved driveway, was now reanimated, a willing co-conspirator as I sped from work to some other obligation in a fit of attention-deficit mania. My bike, for the first time since I was very young, seemed like a lost pet. And then the day came.

It was a beautiful afternoon. I sat in the office, amazed that the legislative session adjourned for the year so early. Redeeming rays of sunlight shone through the only window in our tiny Capitol orifice. I had scheduled an after-work ride with James, another commitment junkie who was, much to my jealously and consternation, in the painful process of shedding his heavy workload in search of some down time.

I was out with him a few weeks earlier at the old Gibbs Farm, where I flatted twice and snapped my seatpost clean off at the rail clamp on a fat log—a good three miles from the trailhead. Mosquitoes battered us like a hot rain and I lost the crown on my root canal. I loved every swollen, dehydrated minute of it, and couldn’t wait to do it again.

But this ride, scheduled for the breathtaking Pittstown State Forest, was canceled on game day because of a leaking tub drain that turned the drywall beneath into a milk-soaked cracker, causing it to yawn away from its joints and eventually collapse into our den. I’m pretty sure that was it; I’d have to consult my records to know for sure. I have mentally buried many of life’s heartbreaking details for want of even a slight wisp of solace.

After a brief game-plan conversation with my wife, I sprang from my office chair and made off to inspect the damage. I called James with apologies, only to have the cell ring again the second I finished the call. It was my boss, who needed me to return to the office to discuss possible changes to a proposed law, on the Governor’s desk and due for signage before midnight. I was almost to my car, a good half-mile away.

But I returned to investigate, all the while preoccupied with the rapidly-depreciating value of my home, the costs that would inevitably ensue and the ever-diminishing daylight that, while not the true antagonist, served as a painful reminder of my now long-gone singletrack fantasies in pristine state forest land. As usual, I sat stewing for over an hour to have a 30-second discussion with the governor’s counsel.

Mission accomplished, I raced back to my car once, fumbled for the keys, and… again the phone! Cell phones are like those little ankle bracelets they mandate for felons under house arrest. It is never good news on the other end, yet people love them. One day someone beside me in a Capitol crapper stall actually answered his phone when it rang, his belt clinking on the floor as he shifted his feet, discussing white pine blister rust in Hudson Valley currants at the turn of last century. I hoped that this caller, the owner of a local nightclub, wasn’t perched on some awful commode while he complained about an upcoming show.

“Your man never came with flyers,” he said.

“I told him to do it before last Friday.”

“Yeah, well he didn’t.”

Something in my chest snapped free and floated up to my neck like a hot spike. I choked it down. You give a guy one job to do besides plug in his guitar and he can’t remember to do it.

“I’ll get on it.”

“Kinda late now,” he said. I liked the man but had no will to debate him, even though he’s an easy, cocaine-befuddled target. The flaws in his character make mine look like quality control standards.

“OK, look, we have a 500-person mailing list, and updated website, ads in all the local papers—”

“Son, the average fella at my club never even finished high school,” he said. “Their idea of a computer is video poker. Most of ‘em prolly never even filled out a job appli–”

“OK, OK. Look, it won’t happen again. We’ll do just fine.”

He then droned on about operating costs and his beer distributor but I cut him short, started the car and put my foot on the gas. After all, there was rapid depreciation going on at home. I didn’t want to miss out.

There is only one stop sign on Dove Street. There is no good reason for it. The cobblestone road intersected by Dove is a one-way and heads nowhere but into a permanent detour created by the construction of the Empire State Plaza in the late ‘60s. Yet the stop sign is there, and I sped towards it when—oh, yes—the phone rang yet again. My wife asked me whether I preferred ziti or vermicelli. A bizarre line I remembered from an early Batman episode came to mind (Batman yanks a noodle from a computer the size of West Virginia, tastes it, turns to Robin and says, “It’s spaghetti… smaller than a ziti yet larger than a vermicelli!”) when suddenly he came out of the corner of my eye, a silver streak arcing to the left in a wobbly death slide.

“Motherfucker!” he bellowed, and clubbed my rear hatch with his fist. I had shot the sign without yielding. I didn’t realize it then, for I was in a lather. Batman, flyers, credits, debits, Pittstown, gasoline, silicone, sparring and dog food filled the brain as he barreled toward me at a mighty clip.

Some are familiar with this state, a preoccupied head hum so rote and so natural that one cannot or would not expend any energy to alter it, any more than one would interrupt the magical Zen state reached on singletrack or in the boxing ring, where all obstacles and pain are handled not with consciousness but by a flawless, floating physicality that guides the spirit towards the promised land.

It almost feels good. But this preoccupation is different, the mark of the devil, for he too is a higher power. His teething spirituality hustles that same thin conduit. I was almost grateful for its sudden dissipation when the guy punched my stupid car, yet I reacted like an overdose case shot back into life with naloxone hydrochloride.

I was pissed off. The bearded, bedraggled commuter was looking for trouble. And I was going to oblige. “Here we go,” I said to myself as I unfastened my seatbelt and looked for a place to pull over. The phone fell to the floor, my wife still on the line.

His torch of brown hair flickered as he hammered towards me, a young and unwashed Daniel Boone in army fatigues and a filthy wife beater. I already hated him. Hated his determination, his bagginess and haughtiness, his lantern jaw and primitive brow. He was out of his saddle, a banana seat bolted to a spray-painted grey frame, perhaps an old Schwinn Phantom tricked out and elongated in the throes of a psilocybin-induced TIG welding ceremony during the Winter Solstice.

It had a hyper-extended fork and the most egregious set of homemade rear panniers I’d ever seen. They looked as though they’d been pilfered from a live poultry market in Queens Village. Bungeed to the rear rack was a tarp-covered mass of goods that swayed as he crunched his single gear. His bike defined him with a precision that made me ache. When was the last time my bike defined me?

This maudlin whimsy was not enough to override madness, however. I jerked over into the next available spot and extracted a large screwdriver from the glove box. He spit on the curb. The window came down as he glided to a stop beside me.

“You got a fuckin’ problem?” was the best I could do. A pitiful opening volley.

“Yeah, I got a fuckin’ problem,” he said. “You didn’t stop at that stop sign, which is illegal, you’re talking on a cell phone while driving which is illegal, and you’re not wearing your seatbelt, which is illegal. You almost killed me, you piece of shit!”

“I took off my seatbelt in case I had to stick you in the throat, you dick,” I said.

Norman Mailer once said that the first rule of dictatorship is to reinforce your mistakes. Evidently I agreed at some point.

“You shot the stop sign. I had the right of way, asshole.”

“Get a life, scumbag.”

“I wasn’t doing anything wrong. So fuck you!” His crumpled brow and almost autistic unwillingness to look me in the face—the expression worn like that of a rudely-awakened general dismissing a messenger—stirred something inside me I had not felt since childhood, the embarrassed anxiety of being wrong and chastened with sickening panache and god-given condescension. This dirtball, talking down to me!

“No, fuck you,” was my brilliant retort, and I wrenched the car back onto the road. As I did so, he was forced to yank his bars up and away to prevent me from clipping him, and his cargo spilled into the street. An old red Jetta screeched to a halt inches from his face as he scrambled for his wares. I sped away feeling like a chump, digesting that debilitating heartburn one gets when backing down from a fight or a hard-won privilege.

In the rear-view, scores of compact discs shattered to earth, hordes of textiles flopped onto parked cars. A radio shattered on a sewer grate. Yet I watched as he knelt calmly, methodically gathering these things while cars leaned on their horns, as if he’d done it 1,000 times before, in chafing February winds, in the smothering humidity of an Upstate summer, on rainy, overcast afternoons and in the lonely pollution of dawn. He never even looked up. And then I remembered something, something shifted, tapped lightly on the breastplate from the inside.

I wove distractedly up toward the light at Madison Avenue, eyes crisp, anger giving way to confusion. The heart tested its visceral tethers but my breath remained tight, a permanent exhale, bequeathed by a lifetime of stress. The nausea of wasted adrenaline poured over me like influenza. I checked the mirror again, and was not surprised to see him coming after me, again out of the saddle. Up from the hill he advanced, expressionless and composed.

I considered dooring him, but another thought occurred, a pang really, a speck of broken language that left quickly, as if to protect the fight or flight response. Thankfully the light changed before he reached me and I breezed through it without incident, winding slowly through Lincoln Park’s recovering magnolias. I looked down at the screwdriver and noticed my phone, open on the floor. My wife! I picked it up.

“Are you all right?” Heather asked. She seemed genuinely concerned.

“I shot the stop sign on Dove and almost hit this guy on his bike,” I said. I could barely choke out the words. “It was my fault.”

“It didn’t sound like it was your fault,” she said, the significance of what happened not lost on her. “You sounded exactly like the person you hate the most.”

It was true. The pangs I tried to ignore, like a fighter must ignore fear lest it negate the power of his punches, was exactly her bold sentiment. I had been compromised. Taken. Beleaguered.

“Why didn’t you just apologize?” she asked before returning to the vermicelli. I had no answer, no reason except anger. Anger, that great prohibitor, making those who would do great and powerful things doomed to lives of miserable ineffectiveness. For how many times had I been sent into shrubbery or split-rail fences by selfish, preoccupied, inconsiderate drivers? How many hairline fractures and sprains, how much proud flesh stretched across this aging organic canvas from spectacular crashes caused by mere caution? By caution! Avoiding those who intentionally tried to split my body into shards? Who flipped me off? Who swore? Laughed? Spit and threw fast food at my face?

What makes us mimic the actions of those we loathe, just as the prodigal son finds himself battering his women and scoring his innards with poison just as he watched his father do so many years before? The same father whose death was a tremendous relief? Doesn’t he resolve that, if nothing else, his life will amount to something different? If not, from where comes the spirit to usurp the daily sickness of the cutworm, the centipede, the cable news, the crushing clasp of commerce?

Incredibly, the cyclist approached yet again as I sat at the Morton Avenue light. He marched up and out of the park. First his bobbing head, then the pumping arms, then his whole body like a piston blown from an engine but still performing its task in perpetuity. His cranks were small, and I knew from experience that pounding up a steep run with them in one gear was no small task. The look on his face never changed as he approached. He wore it like a ceremonial mask. He didn’t even recognize me, or if he did, he didn’t care. Something else called him, worked on him like an exorcism, like gravity.

“Say it,” I could hear Heather say in my mind as he approached. “Call out to him. Say you are sorry.” But he passed quickly, without even a glance, and after he assessed the lower Morton traffic on the fly he sped down into the projects, his hi-tops at three and nine. The tarp was remarkably reattached, as if what happened were a daydream, a hoax. His baggy fatigues snapped repeatedly to his thighs as he coasted, now finally reaping the fruit of his labors, free from concern. Faith in his marrow. Faith in faith. Far too late for apologies, for I was a non-entity. I didn’t exist, and despite my frequency in Center Square, I never saw him again, for I was The Enemy. The Joycean creature, driven and derided by vanity. A lost pet.

There is no good reason for it all.

Keep reading

We’ve published a lot of stuff in 25 years of Dirt Rag. Find all our Blast From the Past stories here.